NOTE ON THE TEXT

This is a strange novelette. Well, the style and framing are strange, at least; the structure and symbols are hopefully more familiar.

I wrote it in 2018, at which time I was reading Matthieu Pageau, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Mary Shelley, Robert Frost, William Blake and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. It returned to mind last year, and I attacked it with some heavy editing, rediscovering in the process the inspiration I received from The Language of Creation, Crime and Punishment, Frankenstein, Fire and Ice, Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening, Songs of Innocence, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Kubla Khan. Symbolism, fairy-stories, archetypes, psychological suspense, lyrical ballads and Romanticism — that’s what I was thinking about at the time.

Perhaps this story belongs here, being the tale of an earnest man in search of an exodus.

~

Peter Harrison

~

PS. I don’t think this novelette will fit in the email; you can view it in full on the website or in the substack app. Better yet, download one of these versions and either print it out or send it to your e-reader to peruse in a more leisurely manner — PDF for printing and EPUB for e-readers:

PDF:

EPUB:

PPS. Alternatively, put on some headphones and listen to me stumble through this reading of it:

ARNOST’S ACCOUNT

So, Mum,

You asked that I keep an account of all that befalls me as I venture north from the city. Here it is. I’m afraid I cannot give clarity to all that has happened; I can only describe haltingly the strange waypoints that have marked my journey.

You may well wonder why my account is written in third-person. I wrote it thus because such was my state of mind. Oft one may discover at a significant waypoint or crossroads how little they know themselves—how false their convictions; how insurmountable their temptations. At such a time, one might feel as if they are dreaming, staring down upon themselves or staring at their own back as they attempt feats that seem too cowardly or too heroic to be their own.

I can only imagine, then, what a parent might think, looking on as their child does deeds that do not seem true to who they are. Perhaps this writing will provide enough abstraction for you to accept the account that follows.

As you know, the city that raised me had an aura of protection. It was protection taken to the extreme—at which point it is detrimental rather than supportive. The city—tinctured by the ice climbing up the ocean from the south—was controlled by an autarch whose ideology aims to eliminate the experience of inequity and, therefore, growth for the citizens of her society.

It will not surprise you, I’m sure, that it was your death that provoked my escape. While most might feel—at the time of their mother’s death—their ground crumbling beneath them, I encountered no such emotion. I was distraught, yes, but my ground was so firm that your passing instead freed me. You always said I would never live out my days in the city. You always knew I would go north. I could not have done so while your life held me there, no matter how much I hated the city. Now, though, I feel your presence just the same wherever I go.

After you passed away west, Father became the head of a secret movement that sought to resurrect the city from its static state. He clung to this hope, refusing to join me when I fled.

I was one of the last who absconded before the autarch closed the city gates for good—she could not control everything that came into the city on the Travellers’ River from the chaotic north, try as she may.

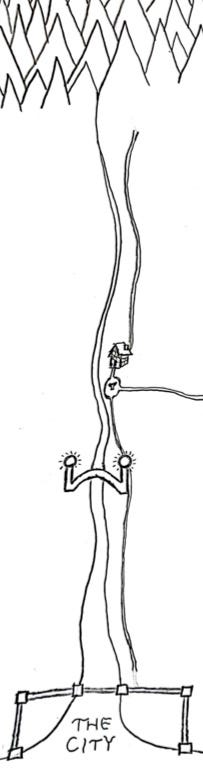

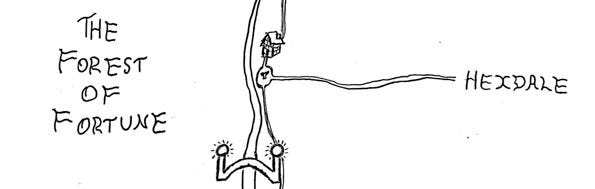

I joined a group of five boatmen who had a life of constant movement up and down the river—fishing and pursuing delivery jobs. I travelled upriver with them—alongside the eerie Forest of Fortune on the western bank and the farmland on the east. An hour or so before dawn, we passed under an ancient stone bridge that joined the forest and the farmland—the copper plaque set into its stones read Cristoforos—and soon after, we found an inn on the eastern bank by a crossroad that wandered off towards the sunrise.

There—somewhere between the dragon of the north and the autarch of the south—I would find the peaceful, carefree life I desired. Even there, however, I was welcomed by the odour of the city, encapsulated in the breath of a man succumbed to his desire to torpefy his life out of existence … And that is where I will begin my account.

Your son in the east,

Arnost

~

PS. Looking back on all that has occurred, I realise that my tale holds some semblance to the events described by an old ballad I heard in my youth. I have written out the song in question and will place parts of it here and there throughout this narrative. It should be effective in establishing what I believe is the crux of the account. Here is the ballad’s beginning:

Harken, good folk of Hexdale Or miss this and pay the price. Cast on fire an unblinking eye And imagine your father in ice. For the bells of the old tower, They call – forlorn – the hour. They chime on high for a dead king, Counting the moments sour.

PART ONE: THE ODOUR OF THE CITY

The sun was crouching low in the east. It cast a kind of half-light—forms of shadow and deep fire—across the ripples of the Travellers’ River, gently flowing southwards from the dragon’s mountains to a dreary coastal city past which the ocean was stagnant with sheets of ice.

Beyond the western bank, there sprawled the most ghostly of all woods—hidden in ash-like mists. On the brighter bank, there stretched a road that ran beside the waterway to meet another path wandering in from the eastern farmland. Where the ways converged, there was a small round courtyard before a lonesome old inn of stone that spouted a steady plume of smoke from its blackened chimney.

Having left their vessel on the riverbank, Arnost and the boatmen were moving up out of the murky, reed-filled gully and onto the cobbled path leading to the edifice. They had paddled through much of the night—by the light of a lilting lantern—and were now desperately desiring to break their fast.

Arnost’s nose twitched; then wrinkled in disgust.

A familiar, unwelcome odour with a shabby leather cap and bare feet was making his way towards them from the inn. The odour swayed, his foot hovering precariously over a muddy hole in the path for a moment before he planted himself firmly knee-deep in it. Sludge sprayed up his leg and spotted his chin. He stood still for a moment, swaying as if he might fall asleep.

He jerked his leg out with a motion that appeared well-rehearsed. Arnost wondered how many shoes the man had lost to the pothole. The odour began to twist the cork in his bottle. He nodded to the boatmen and Arnost as he met them. ‘Beggin’ your g’—here he emitted an ostrobogulous belch—‘mornin’.’

His words—as liquid as his gait—were tainted with the smell of a long night of drinking.

He wrenched the cork from his bottle, threw himself horribly off-balance and stumbled into one of the boatmen, dribbling beer on the traveller’s trousers. The traveller swore and shoved him away. The drunkard toppled to the ground, a gurgle of beer upsetting another traveller. This boatman snarled and aimed a kick at the man’s head. He missed but was satisfied in knocking the bottle from the man’s grasp and smashing it to pieces on the slick cobblestones.

The drunkard writhed, his hands lashing out for his broken bottle, and he cut himself in several places on his stumpy, wet fingers. Arnost watched as the man bled in his beer, unable to find purchase as he tried to rise. Finally, he lay his head in his mess and accepted that he had met his destination: rock bottom.

Arnost wrinkled his nose and stepped over the man.

He cast a glance across the river for a moment. As his gaze found the white fog of the forest on the western bank, a sickening fear grew, squirming in his gut.

Upon entering the dank inn, he encountered a stench even closer to that of the city he’d left behind. Arnost took a deep breath and nearly threw up in his mouth as he sat at the bar beside the boatmen for a breakfast of over-spiced eggs that seemed grotesquely expensive.

I won’t last long out here without finding some work, he thought, and yet, as he ate the eggs, a rare smile flickered across his visage. The inn might smell like the city, but at least he could see the peaceful eastern horizon through the taproom window.

The boatmen had called him scrawny; in truth, he was more than that. He was malnourished, as many from the city were. His face was often expressionless—also a phenomenon of the city. His eyes were dull—but growing brighter as they fought the ennui that had encased him for many years. His pale ginger hair had been black with dense, heavy dye until only a few days ago when, in his vast ineptitude, he had lost balance and fallen overboard—and remembering that escapade, he felt again the strange lightness and clarity that the rushing river water tugging the dye from his hair had given rise to …

Paddling northwards with the boatmen that afternoon, Arnost watched columns of smoke pass them in the east—and he began to tremble.

He had heard of the fierce highlanders who worshipped the dragon, folk who had exiled themselves from the city under the firm conviction that eternal destruction in fire was preferable to a society as brittle as ice. Rumour in the city told of hairy men on wild, mountain-bred horses, eyes ablaze, teeth bared, weapons warm with dripping blood.

Arnost suggested returning to the inn for the night. The boatmen assured him that the zealots never came within sight of the river. Their resolution wavered, though, when the wind picked up, blowing smoke and screams across the river. After a few minutes of indecision, they determined their venture to trade with the herdsmen in the north was becoming too dangerous—they would try again when the zealots had returned to the mountains after their raiding.

Again, Arnost suggested returning to the inn for the night. This time his companions agreed, saying that the zealots never came as far south as the inn …

So, back at the lonesome inn, lying in bed after a large and expensive portion of roasted lamb and flatbread, Arnost had a mind to fall asleep as soon as possible. He had been paddling upriver for the better part of the last twenty hours, had been in more danger than ever before in his life and had said farewell to parents he would never see again. Yes, he had a mind to fall asleep as soon as possible.

He didn’t seem to be able to, though. There was a strange, arhythmic thudding somewhere in the distance that reached through his shuttered window. There were muffled voices in the taproom downstairs … Arnost rolled around in his bed, twisting his blankets about himself and groaning with delirious exhaustion.

Something slammed into his wall, and he spun over to stare at the darkness in the direction of the sound. After a moment of silence, whatever had struck the wall began to crackle quietly like fire. The room suddenly came alive with blazing light as a second arrow struck the inn, breaking through his shutters and impaling the straw mattress on which he lay, an oily wad of burning cloth tied around its shaft.

As the straw caught fire, Arnost threw himself from the bed, clawing at the blankets that suddenly felt like ropes binding him. He burst out of his room and straight into the path of one of the zealots.

Raising a fiery torch with a screaming grin, the warrior’s eyes were filled with merciless hunger as he struck Arnost to the ground.

~

There was a lump like an egg on his forehead when he woke. His nose was bleeding, and one of his wrists was swollen—aching at the slightest of movements.

He found his way to his feet, head pounding and vision swaying across the taproom. Flames licked broken bar stools, and the nearest wine rack lay in smouldering ruins around smashed bottles and curls of smoke.

He struggled to keep his eyes away from the faces on the floor as he stumbled stubbornly behind the counter to pick up one of the partially cracked flasks—desiring for that familiar odour to obscure the death that suddenly surrounded him. He lost his balance, slipped on black dust, and caught himself on the butchered bar. His eyes wandered along it as his hands wrung the bottle.

His gaze found the innkeeper sitting with his back against the bar. A layer of white ash had settled on him, making him appear as a ghost but for the trickle of blood running down the side of his head and along his arm to his fingers, where it split into tiny rivulets and dribbled on the floor.

Slumping to a sitting position, legs stretched before him, Arnost noticed the purse hanging from the innkeeper’s belt. He sighed. That would be useful.

‘Well,’ Arnost said to him, ‘I don’t suppose you need it …’

He remained staring at the dead man for minutes that dragged their feet like prisoners shuffling inevitably towards the guillotine.

‘I could use it,’ Arnost continued. ‘Plus, you all but robbed me with the price of your food. It’s not fair, I know, but it’s not wholly unfair either now is it? And then again, who says the world should be fair? Now I come to think of it, I’d wager you had a life far fairer than mine, here at the crossroads in the heart of the country—here, where people are free … I come from the city, see, and folk aren’t so free there. They work in factories while the sun is in the sky and sleep in sooty beds when the sun is gone …’

A shadow of his old ennui morphed into bitterness as he spoke these words. Such treason against the autarch usually dwelt in vague, unconscious thoughts and dreams far from his waking mind.

‘I’ve escaped that city, now,’ whispered Arnost, ‘but I’m not likely to survive much longer without money for food and shelter until I can find myself a job … What am I saying? I needn’t convince you of anything … You are a corpse, not a soul. What would you care what happens to your money now you’re dead?’

Then again, Arnost thought, perhaps the man was a father or an uncle, and he meant for his means to go to members of his family … Arnost did not dare say these things out loud. In fact, he even forced the thoughts from his mind with further complaints about his lot in life thus far. Perhaps Arnost would have thought on it further if he had received an inheritance from his mother—as it was, the autarch claimed any and all finances ‘owned’ at the time of a citizen’s death. Then again, perhaps in contemplating his mother, he would have only grown more bitter.

He tugged the purse from the innkeeper's belt—the angled blade fell—and his head slumped to the side in response.

One by one, Arnost robbed the dead. He recalled those bodies to his mind many times in the days that followed. He had no memory of the drunkard being among them.

Pulsing coals within the taproom. Waste from a different blight. The grip of ice, as strong as a vice … Our hero’s mien is white.

PART TWO: HEXDALE

On no wisdom but that of instinct and hope, Arnost had gone east, following the crossroad from the inn’s round courtyard. Still wringing the unopened bottle in his hands, he kept his eyes on the horizon with a steely determination to go against that whimpering part of him that longed to open the bottle and stagger drunkenly back to the city.

A few hours later, he saw the hazy form of a town bathed in the gold of the sun that dipped low behind him, stretching his shadow painfully onward before his gaze. The glory of the hour was lost on him, as he was not used to seeing his shadow. It was ordinarily hidden in the obnubilation of the dense buildings that cast the houses of the city's denizens in disillusioned darkness.

The town grew clearer as he approached—thatched rooves, mud-brick walls and wooden doors with bright knockers. Comfortable, quiet and seemingly warm despite the cool breeze pressing up from the south. The wooded hills rising beyond the buildings gave a sense of balance to the heavy red sun setting in the west. They also contributed to the sense of the town being held in a little nook of welcoming serenity.

He found the public house with little trouble, for it was pleasantly placed only a few houses along the main road—between a tailor’s and a brewery.

An eruption of sound enveloped him as he pushed open the door. As he closed it, the cacophony morphed into a jaunty tune. The occupants of the room, though seated here and there and obviously being comprised of at least four separate groups, were all joined in a lilting tune. As the ballad ended—in a barely mellifluous fashion—Arnost sat himself at the bar. The innkeeper made his way over to ask what he’d have.

‘A room for the week?’ Arnost asked. His eyes swept over a fireplace by the eastern end of the room before they settled on the innkeeper.

‘Of course, Sir. And a drink and dinner?’

Arnost’s gaze fell to the bottle in his hands. He lifted it towards his host, saying, ‘Just dinner, and could I pay part of my board with this?’

The man took the bottle and inspected the label. After a moment, he raised his eyebrows, shrugged and nodded his ascent.

~

Arnost joined a group by the fire later that night.

A boy brimming with freckles had claimed a spot between an elderly man and a hulking specimen who, Arnost guessed, was a blacksmith—and beside whom sat a young woman, holding her knitting in her lap. Arnost found an empty chair beside the knitter as the elderly man said something in a gravelly voice.

The boy interrupted. ‘Why didn’t he go into the forest, Tanner?’ he asked.

Tanner—apparently in the middle of a story—gave the boy a grave look, narrowing his thick eyebrows. ‘Because nobody with any sense goes into that forest, boy.’

The big man nodded seriously.

The woman raised an eyebrow, glancing at Arnost as he settled himself on the seat.

Tanner was nodding slowly, staring at something only he could see. ‘Where was I?’ he grumbled.

‘The girl was taken into the forest!’ said the boy, licking his lips and tapping his heel on the floorboards.

Tanner continued to nod. ‘That she was,’ he said. ‘A dark and gloomy place the forest is, but the beast knew well the twisting paths and dragged its hostage along through the damp, decaying leaves. Its den lay deep within the bone-white trunks …

‘The knight stayed on the bridge, for he knew that he would die if he followed. The girl would be eaten by the beast, and he must wait in the east to have his vengeance when it returned.’

Expression indignant and voice rising, the boy stopped tapping his foot. ‘That’s not how a story ends!’ he declared.

‘It ends how it ends, boy,’ said the blacksmith.

Tanner grunted something noncommittal.

‘But,’ the boy protested, ‘the Forest of Fortune is supposed to give the hero … fortune!’

‘A foolish superstition,’ said Tanner. ‘The forest gives only death.’

The blacksmith leant forward. ‘It gives you redemption, though, doesn’t it?’

Tanner glared at the pair of them. ‘I suppose one could find redemption there—were they a wretch seeking death in atonement … The jackal in that wood is worse than rabid. Its eye is malevolent and its bite is merciless …’

After a moment of silence, the old man’s scowl broke, and he chuckled and nudged the boy affectionately. ‘Perhaps you can tell me a better ending to the knight’s quest tomorrow night.’

The boy’s eyes lit up.

Tanner stood. ‘I’d best be going.’ He glanced at the woman knitting beside Arnost as he shuffled to the door. ‘See you in the morning, Avil.’

The woman smiled and nodded in response. Soon after, the blacksmith and his boy left as well.

Arnost sniffed and scratched his nose, watching the two leave.

‘From the city?’ The knitter had not looked up. ‘I’ve heard it’s cold down there …’

Arnost’s eyes wandered back to the fire. ‘Getting colder,’ he said, not looking at her. ‘Not so comfy as here.’

His fireside companion smiled, having ceased her knitting to observe the dancing fire as she said, ‘Yes, Hexdale is a comfy place.’

‘Hexdale. Well, it does feel magical …’ Arnost admitted, picking at the blood dried to his shirt, ‘but hexed?’

The woman shrugged, watching his efforts. She put her knitting aside completely. ‘What’s a man from the city doing this far north—and covered in blood and ash, no less? I’d like the whole outlandish story, if you wouldn’t mind.’

Wondering where to start—and experiencing a sudden strong desire to not hesitate and appear awkward—Arnost blurted out, ‘My mother was the reason I stayed. When she died … I left.’

This gave the knitter quite an awkward pause, of course. She nodded slowly and asked, ‘What about your father?’

‘He stayed.’ Arnost replied. A memory of his father sitting in a rocking chair with a bone needle between his fingers flashed before him—the smell of soot in the man’s hair and the brick dust on his boots … ‘I tried to convince him to come with me,’ Arnost continued, ‘but … well … he is committed to an effort to improve the damned place. It’s a hopeless endeavour, I think.’

‘And what are you endeavouring to do here in the east?’

Arnost grimaced, finding an uncomfortable barb in her question. ‘I want to find somewhere I can be happy—and people I can be happy with … I used to tell myself I wanted to be carefree, but I now think I would just settle for being free and perhaps only needing to care about work that is honest and rewarding.’

The lady sighed, meeting Arnost’s gaze with empathy and affection. ‘Comfy as Hexdale is, folk here still worry about more than that … There are the zealots that ride down from the north, you know—they seldom come this far, yet with each raid, their fire reaches further …’

This gave Arnost pause. He nodded slowly. ‘I know something of the zealots. They are part of the outlandish story of my arrival here.’

His companion took up her knitting again, grinning and nodding energetically. ‘Yes, on with the tale, please … How did you end up covered in ash and blood?’

A smile lightened Arnost’s face at the excitement in his audience. He went on with his tale, and the innkeeper decided to join them—somewhat to Arnost’s annoyance, as he had been enjoying the undivided attention of his new acquaintance—and the three of them talked until the grey vapour of dawn had crept across the taproom windows.

Arnost bought a new shirt the next day—and new thick-soled shoes. He picked flowers for the lady, and she invited him to have dinner with her and her grandfather, Tanner.

Suffice to say that a pleasant time followed his long conversation with Avil and his days of lodging at the Milky Inn. She took him to cheerful nearby settings—like the waterfalls, rock pools and wooded glens of wild roses that wandered further eastwards. They ate pastries and drank strong tea thick with spices and honey. He found work as a farmhand—and thus began to learn about the processes of raising unruly goats and making butter and cheese—and she told her grandfather she quite liked him.

Arnost wrote a letter to his father, telling of his safety and his joy; he received this response a few weeks later:

Arnost Ordalson,

Your father (Ordal Eveningson) was, last week, banished from the City of the Third Autarch of Concord for the possession of artefacts in violation of Her Magnanimity’s Indubitable Law concerning the defacing of her sympathetic figure, and he has boarded the ashen ship bound for the western forest.

Your father’s fate is set in ice, but the redemption of your family is in your hands. Return to the bosom of the city—repent—and your legacy may yet be vouchsafed.

Regards,

The Office of the Autach

The benign king trapped in dead, dark trees On death’s own forest floor. Moments of terror set Against the god of gore. To cut his soul, the hero must learn. And to see the great grey ghosts Of ages past; ages to come. Ere he burns his heart most.

PART THREE: ASH AND THORN

Mist, thick and harsh like a cloud of ash, billowed from across the Travellers’ River. The broad, black waterway was eerily silent; silent as death; silent as the deep, empty ocean beyond it. When the wind blew, the skeletal trees groaned—low and menacing.

Arnost watched the mist approach from across the river. His face was slack, his flesh filled with trembling fear as he searched for what stoic courage might dwell somewhere deep within him, buried in its own neglect.

Enough thinking. It was time he got on with it—whether he was courageous enough or not … That was something his father used to tell him … ‘Get on with it,’ he would growl affectionately as he dishevelled Arnost’s hair.

He went forward.

As Arnost reached the bridge, he looked up at the lampposts on either side of the path. Small flames flickered within them, too distant and diminished to lend him any warmth …

And Cristoforos bore him across the river towards the forest of crooked, bare-limbed fig trees. On the other side, he stepped off the bridge and onto the black, decaying leaves—and hidden thorns dug into his shoes.

The ground was broken with muddy pools and rivulets—and when he threw his gaze upon the skies, it was only to see that the moon had plummeted, leaving only velvet obscurity. The earth had become the heavens, and the stars shone below him like an ocean of lost aspirations. The great river emptied itself into this abyss and was lost beside the moon that continued to shrink into the dark void that was the old heaven.

The cloud of ash engulfed him.

Through tangled roots with cruel thorns thick And over the dark morass. Across the waste of wraith-like trees, In pooling blood, he sees: His father struck with mortal wound On a bed of icy thorns. With his great red weapon out of reach And the hound approaching – approaching! With a cry like life; mocking pain Our hero leaps and lands Between his father and the hound He draws his sword and demands: 'Harken, hound of death’s own army; Jackal of the white wood. Leave now and return to the grey, Ere I kill you – I should!' The hound, he howled and shook his jowls. He raised his ghastly hackles And pounced with bloody paws upon Our hero like iron shackles. And a tussle took place betwixt The two who yelled and growled. Our hero was driven back again; Across the icy ground. And his blade – beaten from his grasp Flew far across the thorns. The beast closed in with dripping chops A devil without horns. But his father’s sword lay near enough To sweep up off the bed. Our hero drove it through the jaws Of death and red it bled. His father cut free of the thorns, Amidst the ghostly trees … Step across the long cold bridge To the land of living leaves …

His father had a thick grey beard filled with the ash of the woods. His clothes were torn and his chest was heaving as Arnost sat him up against one of the lampposts on the eastern end of the bridge. The light above Arnost seemed closer now, showing him where to sew. With his father’s bone needle, flax thread and river water, he cleaned and closed his father’s wounds.

His mouth was fixed with a grin that made his cheeks ache.

‘Do you think you can move?’ he asked, struggling not to laugh for his giddiness. He went on without waiting for an answer. ‘Dawn will come soon, and you can meet Avil. Hexdale is peaceful and pretty, Father, and smells of milk and roasted meat and—’

‘It sounds like a lovely place, Arnost,’ his father broke in, ‘but I cannot go.’

‘Nonsense. It won’t be any trouble.’

‘It is not the trouble, Arnost.’ His father sighed, pushing himself a little further upright. ‘I must return to the city.’

Arnost stopped, his eyes losing focus for a moment. Shock and stinging pain filled his vision—as if his father had cuffed the side of his head. A little part of the city boy within him perished right there on the bridge as he knelt with the bone needle hovering above his father’s chest. He swallowed, continuing his work silently.

‘Arnost—’

‘You’re delirious, you’ll see,’ the boy murmured. ‘The dawn will come and … you’ll see.’

‘I must go back to the city.’

Arnost tied off the thread with a brusque motion that verged on a savage jerk. ‘The city is horrible! Hideous …’

‘Listen, Arnost …’ His father’s hand came to rest on his shoulder.

The final pillar of his youthful vision gave way. That heavy hand was love and warmth and calm … calm waters. Arnost’s shoulders shook, and tears spilled out between his closed eyelids. He dropped the needle, and his father came forward onto his knees to wrap him up.

‘Why?’ the boy whispered, pulling away.

‘My city can be redeemed.’

‘It’s not yours. You don’t belong there. You had no part in making it what it is …’

His father sighed. ‘Didn’t I … Well … I have a chance to make it what it could be, to break the ice that blankets that ocean. I have a following. People believe … They believe that things can change.’ His father rose, picking up the needle. ‘The city will change. The ice will melt or shatter.’

‘I will come with you, then …’

‘And what of Avil?’ his father said. He held forth the needle. ‘No, Arnost, I think this world is yours. You were never meant for the city, I think …’

‘Just come to Hexdale for a week … a day …’ Arnost pleaded. ‘Meet Avil. Walk in the woods and pick the wild roses ...’

‘I fear I would stay forever and forget the city.’

‘They will execute you.’ Arnost took the needle.

His father chuckled. ‘They have already tried that. No. I must return.’ His father closed his son’s fingers around the needle. ‘We will see each other when the south knows summer and the north is cool with winter’s breath.’

Arnost sat—defeated—on his heels with the bone needle between his fingers.

PART FOUR: IN THE BALANCE

He put that needle in the chest pocket of his shirt as he took the path to Hexdale once more. He felt the larger stones of the path through his shoes, for the thorns had worn them down.

He thought of what the city would look like if his father succeeded. He thought of rose bushes and maple trees littered throughout the streets instead of the broken bottles, beer and blood …

As his mind wandered, he did not notice the glow in the east between him and the wooded hills. It flickered into life before the grey of dawn began to filter through the air. Arnost only saw it when the two colours started to mix. The pallid grey and stark orange above the crooked horizon; the smoke rising in thick columns.

His mouth clamped shut as he jerked forward into a sprint. He twisted his ankle on a stone and fell, grazing his hands and knees. Gaze fixed on the fire, he rose again, blood dripping from his fingers, gut sinking, heart pounding and breath catching in his throat.

Tears rolled from his eyes like wax melting away from a flame. He limped onwards—too late to save his little nook of comfort nestled between the pleasant woods and open farmland. His paradox of peace balanced on the brink of the heat and cold; far from the western banks of death.

By the time he arrived, the conflagration had caught the woods beyond the village and was still roaring as it rolled eastwards. By midnight, it had begun to rain heavily, and the flames in the trees hissed their disapproval like a thousand seething snakes as he slowly ceased his wandering through the ruins and the devouring heat.

The zealots had reduced Hexdale to rubble. The bodies of Avil—and a number of other people—Arnost could not place. He wondered if they were among the unidentifiable corpses or if they had been captured by the zealots.

‘It is all for nothing,’ he told himself—in a voice that belonged back in the city.

‘I know now that living in the north makes little difference to living in the south, for by the will of the heat or the cold, we shall all be taken into death or unconsciousness. If we are not dead or unconscious, we are in pain, and this pain is worse still. Perhaps I shall cut out the worst and make the most out of what is better: death or a torpidity that leads to deathlike unconsciousness?’

This he said in pain—and in fear of pain—but the unplanned words that he uttered gave him pause, for though pain was more terrifying and difficult than death and unconsciousness, he knew it was the only path with any hope that went beyond numbness.

‘No!’ he said to himself in desperation. ‘I cannot face the pain. I will end myself, for what then could I fear?’

A truly sinister idea followed those words. It was an idea firmly rooted in the fear of death he had told himself he could overcome. It spoke these words in a quiet, cowardly voice:

If life should end, it should end for everyone—not just you.

A bleary picture forced its way into his mind’s eye: the other boys from his school in the city. They would rebel as he did, and they would be in the same pain he was in now—before they were killed or gave their consciousness over to the autarch’s ideology. Why not save them from this pain? Why, if this world was tragic, should Arnost let the pain continue?

‘It is all for nothing,’ he repeated with a little more despair, fear and finality.

And it may have ended there if he hadn’t reached into his pocket and taken out his father’s needle, pricking himself as he did so. He wasn’t sure why he took it out, but suddenly his eyes were locked onto the smooth bone as his father’s voice echoed through his head:

‘… they believe that things can change.’

The rain fell in thick blankets, extinguishing the flames before Arnost and leaving the ancient, wizened trunks still standing. Shoots will grow, he thought to himself, and more of his father’s words broke into his aching mind.

‘… the ice will shatter.’

Heat and cold were conquerable. To kill himself was to say that they were not; to add to the suffering he so despised. To try to quench the fire—to hope that Avil was alive—was to declare and to pray that the pain was bearable.

If fire could be tamed, then what he should truly fear was not taming it. A world of people who murdered in despair was something far worthier of his terror.

A long, deep rumble came from the north—as if responding to his thoughts with a challenge. It shook the ground—and his core shuddered. His vision blurred for a moment, making the trees of the woods appear as thin spectres and the flames as fat red leeches dancing around them. The roar ended, and Arnost had that same strange feeling as when he had fallen out of the boat escaping the city—the feeling of the dye coming out of his hair …

He left Hexdale at once, tracking the zealots north into the dragon’s mountains.

Mum,

I am now sitting on a stone in the snow, atop a monstrous mountain, beside the maw of the cave from which the Travellers’ River is birthed. Behind me there grows a colossal tree with ancient gnarled branches worn bare by wind and sleet. In the twilight, I fancy I can see pale grey flames dancing in the crevices of the bark.

The zealot’s tracks—and the river—led me here, above the dispersing ash-like clouds.

The world is open before me. The river flows down to the distant ocean, where the ice halts before the city. The tangled mass of the Forest of Fortune fills the west for as far as I can see. The pleasant farmland and woods of the east look rather empty … but on my journey, I have met many who live there.

When I first found this cave, the mountain shook beneath me as the dragon roared again, and my father’s needle suddenly began to burn in my pocket. Taking it out, I saw that it was glowing white-hot.

The dragon continued to roar, and the needle began to transmogrify. It elongated, then broadened and grew heavy. It became a sword. Its blade was white bone and its hilt was wrapped in leather from some scaly beast’s hide.

I shall now go through the mouth of the cave—maugre my writhing fear.

Please pray for me, Mum; give account of my trespassing and plead for my deliverance through the baptism of blood and fire that draws near.

Your son, trembling,

Arnost

PART FIVE: BLOOD AND FIRE

Down.

From beside the bubbling spring that began the river’s gentle southwards flow, Arnost peered down into the darkling stone maw.

Through pure white snow, he dragged his grime-encrusted, road-weary shoes—soles once thick and soft were beaten hard and thin with the walk from Hexdale into the mountains. Through the harshly cold alpine air, the blade of the sword in his hand cut with whispered indifference, quietly questing for its foes. Together, they would venture down into the darkness, Arnost and the sword …

Down.

As Arnost entered the cave, the wind died away. In place of its cold vitalisation, a roiling warmth met his arrival with a crocodile’s grin that went beyond welcome into the hunger of an alien host. In place of alpine clarity, a seething, smoking gloom seeped up through the deepness to confront him.

The stone floor of the cave sloped downwards, gradually steepening until—only a few dozen metres into the darkness—Arnost was forced to lean back onto his hands and scoot forward slowly, fearing a slip and a sudden fall of an unknown length. It soon became apparent that this parabolic decline would force a commitment to the drop, for he now recognised that it had grown too sheer to climb back up the slick stone behind him and would quickly become too precipitous ahead of him to control his descent. Thus, he would either remain frozen until his muscles gave out or he would leap forward—and down.

Arnost filled himself with a slow, even breath of the stifling cavern fumes, then pushed hard off the rock and into the hungry emptiness that awaited him.

As he fell, a vivid memory came rushing into his mind to save him. He remembered a waterfall that Avil had taken him to—during his week with her in Hexdale. They had climbed to the top of the fall, and Avil had pestered and poked him until he agreed to jump off it with her into the pool below. He remembered the stinging slap of the water on his skin as he landed—and the thought came to him that if he were right now falling through darkness into water, he might reduce the danger of landing by tossing something ahead of him to break the tension of the pool.

The heat intensified as he fell, and a glow of mingled green and deep red began to emanate from below him.

With fierce desperation, he struggled awkwardly to get his arms free of the straps of his rucksack, swapping his sword from one hand to the other to achieve the feat. Thrusting his rucksack down ahead of himself in triumph, he heard the splash of it meeting water just below him—just in time.

Utterly submerged, Arnost knew immediately that the liquid around him was not water—or, at least, not only water. It was too thick and too globular in texture. His fingers encountered coagulated parts in the liquid around him, and he had an almost overwhelming convulsion to be sick.

The next thing that he noticed was that something was dragging him down by his hand, and he opened his eyes on reflex to discover what it was. Eyes instantly stinging in protest of the foul, encompassing liquid, he saw that it was the sword he grasped that was pulling him down. He did not think it was heavier than before because it seemed to be drawing him at a slight angle—towards the source of the heat and the red-green glow—and not directly down.

He needed air, though, so he fought the sword’s will and swam for the surface. Head breaking free of the bloody water, he gasped and cast about for some stone to gain purchase on. He spotted the silhouette of what appeared to be an island floating on the surface of the water. He swam towards it, aided by the fact that the red emanation his sword was drawn to was in the same direction. As he came nearer the dark mass, he found that it was, in fact, floating directly above the source of the heat.

Arnost clambered onto it, finding its structure ribbed and tangled like the roots of an ancient tree, and he wondered if it was some poor dismembered part of the great tree growing on the summit of the mountain he had left behind—a tree whose timber was not easily given to petrification and, therefore, drowning. It gave him some solace to think that he was supported by part of a tree that refused to decay or burn even in the jaws of the dragon’s den.

The dreadful underground lake shuddered around him as he caught his breath. It set his little floating island rocking in the sudden waves that lapped at the distant walls of the dark cavern. Arnost crawled to the edge and peered into the red water, trying to pierce the greenish glow in the distant depths as he planned his next movements. He imagined he saw some immense black, serpentine form shifting in the heart of the heat, causing the whole lake to ripple.

He had tracked the zealots who had taken Avil, and the tracks had led him to the cave at the summit of this mountain, which meant that they too had dropped into this cavern. Where had they gone from here? Arnost could only assume they had gone through the bloody water and into some cavern beyond this one … It seemed like just the kind of deeply macabre entrance that a dragon’s zealot would use.

‘Right, then, sword,’ Arnost said, having regained his breath enough to whisper into the darkness, ‘you seem to know the way …’ He climbed to his feet, squaring his shoulders and admiring the weapon in his hand.

‘Lead on,’ he said—and dived again into the blood.

Down.

Deeper.

The sword pulled him doggedly onwards into the red glow and boiling heat. He found the shifting shape he had glimpsed from the floating island. It was a gargantuan forked tongue, flicking this way and that, tasting the bloody water. It—and the heat and light—came from a crack in the stone bed of the lake.

His blade gained speed as he approached, and he was forced to close his eyes as plummeted through the water. The steel met flesh and parted it. Arnost came to a stop and opened his eyes. The sword was embedded halfway to its hilt in the red tongue, which instantly began to writhe and retract through the crevice in the lake bottom.

He clung desperately to the hilt of the weapon, and the tongue drew him through the crack into ever more searing heat. As he was buffeted and scraped by the rough stone sides of the tunnel the tongue was retracting through, he was struck by the bizarre notion that he might now think of himself as the most suicidal fisherman to ever plumb the depths of any of the world’s waters. He was bait, hook and sinker—but there was no string to pull him out again.

Even in the exigency of that situation—with the tongue now pulling him sharply upwards—Arnost could not help but laugh at his own more-than-manic joke. Just as the laughter broke from him, he was pulled free of the bloody water—and he entered into the strangest moment of his extraordinary existence.

To understand that moment, one might first need a short description of the layout of the caverns into which Arnost had ventured. You see, the dragon dwelt in a cavern adjacent to the lake, yet slightly higher than the level of the water. The zealots did indeed enter this most sacred cavern through the tunnel of blood-water—and the dragon drank by threading its tongue through that same crevice …

So, when Arnost came soaring from the tunnel—scraped and bruised to bleeding nearly all over—there was a moment between the water and the dragon’s jaws where he saw the zealots arrayed before the beast, offering praises and a prisoner—Avil!—for its pleasure.

And the zealots and their prisoner saw Arnost, laughing like a maniac at his own joke in the disappearing seconds before the shining red-green dragon ate him—bait, hook, sinker; all.

In, Arnost went, and down.

Deeper.

Rather than trying to wrench the sword out of the serpent’s tongue, Arnost braced himself against the inside of the beast’s throat and tried to push the sword deeper, through the tongue and into the flesh beyond.

The zealots and the prisoners saw the point where his sword pressed against the inside of the dragon’s scales, a swelling descending towards its belly as it swallowed Arnost. It began to choke, for it was, of course, also swallowing its own gigantic tongue.

It writhed, trying desperately to breathe or to roar, until it gagged and vomited.

Out shot the tongue again, and Arnost with it. The force of the expungement even loosened the sword. Arnost went flying into—you wouldn’t believe it—Avil, knocking her out of her captor’s arms.

The two of them went rolling, covered in the oozing enzymes of the dragon’s gullet. This was fortunate, as when a dragon vomits, there is certainly fire involved, and nothing saves one from dragon fire quite as well as the ooze that protects the dragon itself from the flames within it.

So, fire followed close on Arnost’s heels and ravenously consumed the zealots around them—and after fire flowed the dragon’s blood. The beast devolved into an agonised fit of coughing blood and fire intermittently from its injured throat, filling the cavern with flashes like fireworks and the stench of frying human and dragon flesh.

Arnost and Avil climbed to their feet amidst this demonic display and looked desperately about for an exit. Avil grabbed his wrist and pointed to the far wall of the cavern. She shouted something that Arnost did not hear over the roaring, spluttering dragon. Following her finger, though, Arnost saw what she had found.

Halfway up the wall of the cavern, water came tumbling out of the rocks, filling a small stream that led to the tunnel, which in turn emptied into the lake.

Together, they went for it, and as the dragon choked on blood and seared its own throat—drawing near to the point of suffocation—the lucky couple climbed up over the stones and out of its dreadful den. They followed the happily trickling water up and away from the dying dragon. When they could no longer hear it thrashing, roaring and coughing, they began to laugh and cry merrily despite the utter darkness around them.

After a few hours of trekking along beside the stream, they emerged from the darkness onto a mountainside of rugged rock and budding heather—and under the glorious gathering yellows and oranges of a soft sunrise. They emerged beside the broadening Traveller’s River—of which the stream they had been following was a thin off-shoot—about halfway down the mountain.

They sat together and watched the sunrise, and Arnost proposed to marry Avil, of course, and she accepted, and they supposed that they would return home to Hexdale and that from then on, they might live happily—and with any children granted to them—in the peace and hidden beauty of that village which they would rebuild.

So there was a joy on that mountainside such that Arnost composed these three verses for Avil:

Of ice, death and flames, I have tasted. Of time, water and names, I have wasted. And now, sad of all Endless circling natures, I hear a selfless spirit call, And offer up my wages. For a blossom has softened My wayward, wanting heart. Avil, I am coffined, So never will we part.

And there in the dragon’s mountains, a cool wind budded with the heather, and turning south, they thought it looked as though the distant ocean was bluer and less frozen than it had been …

And it was spring, I suppose.

(END OF NOVELETTE.)