This is the third of five instalments. Here are the other instalments, in case you are up to a different one:

Part One: The Janzacs of Hazathsad

(You are here.)

Part Four: The Burning Janzacs

Part Five: The Birth of the Taranor

And here is an audio clip for those who’d prefer to listen to a reading by yours truly:

PART THREE: THE GOLDEN JANZACS

CHAPTER NINE: JOURNEY INLAND

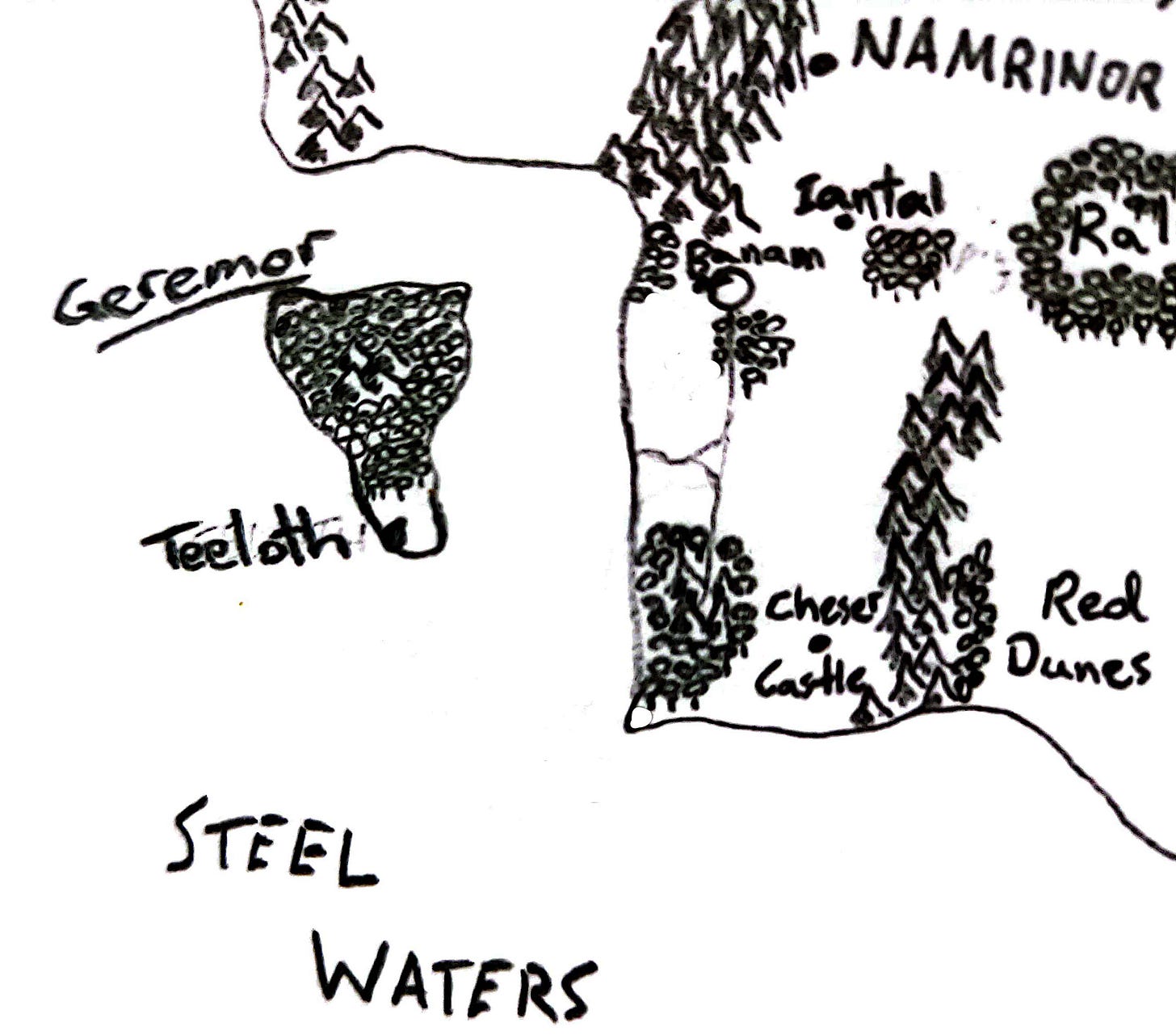

In the woods of Geremor, the crew had spun their own cloaks and cowls. These helped them hide from the mobs that went hunting for them every few weeks. They also, when the cowls were drawn, masked the most obvious telltale signs of the Janzac: the streaks of blood-red hair and the double irises. They all had longbows and arrows they had fletched themselves. Janzac battle-axes were quite recognisable too, so they had hidden these in their travel packs when they stole into Teeloth at twilight.

When they saw one of their pamphlets tied to a lamppost on their way to the docks, it was a cherished sip of hope—the first sip they’d had in some time. Though the pamphlet had been obscenely defaced, it was still proof that the knife-thief Geremorian believed them. There was at least one non-Janzac in Durnam sympathetic to their cause.

Cowls shadowing their eyes, the Janzacs took the twilit ferry to Iantal Province. They hoped that the further inland they went—the further from the torches of the Janzacs—the less hostile the people they spoke with would be.

Gallamis struck up a conversation with the ferry conductor when they were a few hours out.

‘News from the Isle of Mija recently?’ he asked at one point, leaning on the stern railing beside the Iantalian. It was most likely that the Janzac king would begin his conquest there.

The conductor shrugged. ‘Poor buggers are still getting hammered harder than anyone else by the devil-eyes,’ he grunted. ‘Gambatorj is all but ruins, I hear.’

Gallamis nodded, watching the churning wake of the boat as starlight slowly replaced dusk.

‘Word is, they’ve planted a permanent settlement on some island north of Rüded,’ the man continued. ‘There’re a few villages on the coast there getting pillaged real regular.’ The man spat into the ocean. ‘Poor buggers,’ he said.

They landed under cover of night and slept outside the town, rising early the following morning to begin their journey northeast.

Before Iantal was obliterated during Vonhoroth’s Final War, it was the most beautiful place in Tinoyamen. In the months of wandering travel towards the capital, the recalcitrant Janzacs saw much of its artistry and splendour.

They found that their prediction was correct—that people were indeed less suspicious of Janzacs, the further inland they went. Circling their way towards Iantal City, they got work in what towns they could, slowly building a reputation for the quality of their labour—if there’s one thing Iantalians know, it’s quality artisans. As you know, I’m sure, people began to refer to them as the Golden Janzacs. My father, Coran, was the most recognisable in this movement, for, as I have said earlier, he was certainly an artist with a fine eye for detail and dextrous hands.

This stage of their life lasted nearly a year. It was probably the best year of most of their lives, and its greatest stroke of luck landed in its final weeks.

By virtue of his growing reputation, Coran once had a courier stop him in the streets of town a few miles south of the Weeping Woods. The courier gave him a letter that was a request for his presence in Iantal for the completion of a job—the shaping of an ornate door for the resident of a house in the inner-city quarter. The man had heard about him from a cousin in Fort Banam and was willing to give him residence for the duration of the job—both because a Janzac wouldn’t be allowed to stay in any tavern and because he didn’t want to be seen inviting a Janzac into his home each morning.

The crew had not ventured into the city and were hesitant at first, for larger cities often had more distrust for Janzacs than inland backwaters. But, after careful deliberation of the offered payment in the courier’s letter, they decided Coran should take the job.

So, sometime in early spring, Coran made the journey into Iantal City, cowl pulled over his head and eyes bathed in shadow.

CHAPTER TEN: THE IANTAL JOB

My father met my mother only three days into that job.

He was fashioning a door of darkly veined plum wood. Set with many panes of stained glass in odd shapes and at strange angles, it was a tricky task. The owner of the dwelling was an old leatherworker by the name of Brenton. Many years later, when he passed away after taking and training a Janzac apprentice to replace him, I would go to that shop almost daily to read and to work on this story. It was a refuge of mine in the wake of my mother’s death.

When my father worked on the door there, it was a similar place of bustle. The scent of his wood chips and oil would have tinctured the underlying smells of tanning leather, wet glue and shoe polish.

The door in the storefront—soon to be replaced—was only hip-high, and it rang a small bell overhead when someone pushed through it.

The woman closed it behind her as she observed the interior of the store.

She was of distant elfin lineage, so her eyes were fey, and her long dark hair often seemed to shimmer with the faintest of blue or purple tones. These fleeting intimations of colour had the odd effect of drawing an observer’s attention to the depth of her hair’s ebony hue rather than away from it.

Her gaze settled on the only other person visible, a hooded man chiselling a groove into a long stretch of wood on a table in the workshop beyond the store. She watched him for a moment through the open door of the workshop before Brenton slipped into the store from a side entrance.

A welcoming smile spread over the leatherworker’s face when he recognised her.

‘Welcome, my lady,’ he said cheerily. ‘What can I do for you?’

‘A book cover, if it pleases you, sir,’ she said, holding up her new journal. ‘I had one made here last year that was quite fine, and I thought I’d come and see the store …’

‘Well of course!’ said Brenton, who remembered well the hours he had put into the floral patterns on the previous book cover when he had received the order from the palace. He also remembered well the payment he had received. It had probably ended up somewhere around his second chin—that was where he thought all those delectable pastries went, at least.

‘If I could just take a few measurements of your journal, my lady,’ he said, ‘I can get right to it.’

‘You’re too kind,’ the lady replied, handing over her journal as the leatherworker pulled a wooden rule out. At length, as the craftsman started taking notes, she asked, ‘You have a carpenter in the workshop at the moment?’

After a slight pause and a glance in the direction of the cloaked man, Brenton nodded. ‘New front door in the works, my lady,’ he said, motioning to the one she had entered through.

She returned the nod, glancing again at the stranger just in time to ever-so-briefly catch his uplifted gaze before it fell to his work again. She froze, the man’s royal-blue eyes—ringed with a sharp light-grey—imprinted upon her mind like a signet ring’s stamp.

Brenton, noticing her sudden tension, made a speedy final measurement, recorded it, and held her book up for her. ‘Thank you very much,’ he said, louder than he had intended. ‘It shan’t be more than a week, I’m sure.’

‘Thank you,’ she replied slowly, tearing her gaze away from the man and receiving her journal. She walked home very thoughtful and, of course, very intrigued.

The next day, when she walked past the store again, she couldn’t help but poke her head in. The cloaked man was still there, working on the door, and Brenton visibly paled when he saw that she looked straight for him.

‘The honour is mine again, my lady,’ he said quickly, hoping his smile was more convincing than it felt, stretching painfully across his protesting features. ‘How can I help?’ He was in the middle of his lunch break, and a gorgeous beef-and-pepper pie was on the counter in front of him.

‘I just thought I might like to take a closer look at the door under construction,’ the lady replied.

Brenton was sure that his next few movements were anything but elegant, and the spluttering that exited his mouth made him blush crimson. But, knowing he couldn’t very well refuse the praetor’s daughter, he eventually nodded, swallowed, and said, ‘But of course, I’m sure he won’t mind.’

Coran did mind, of course. It made him just about as nervous as sailing into Whiterock Sea, in a strange way, when she pulled a chair over to watch him measuring out sections for the stained windows.

She was used to people introducing themselves to her—or, at the very least, acknowledging her presence—long before she was obliged to do the same. So, when Coran pretended to be so intent on his work that he didn’t see her sit down, she cleared her throat, and he was forced to give up on the vague hope that he would be able to keep his obvious ancestry secret from her.

He set his eyes, the strangest she had ever seen, on hers again—the strangest he had ever seen, tinctured as they were with her elfin heredity. They beheld each other silently for the space of a breath—and, watching apprehensively from the store, the leatherworker held that breath quite a while.

When, at last, he was forced to let it go—audibly—they both glanced at him, and he decided to pick up his stylus and become intensely interested in his own work. This happened to be his lunch, of course. Having stabbed his pie with a silverpoint stylus, he cursed under his breath and accepted that his life was likely forfeit for harbouring a Janzac.

Coran’s gaze returned to the praetor’s daughter when she laughed softly despite herself. The Janzac decided the game was up if he didn’t start making a good impression soon.

‘A pleasure to meet you, my lady,’ he said, brushing his cowl back. ‘My apologies, my name is Coran Tarrathonson.’

‘Olivanin,’ she said, offering her hand.

When he shook her hand—instead of kissing it, as was customary—she laughed again. This threw Coran, and he wondered if she was one of those crazy people who laughed when they were about to do brutal things—like ordering someone executed for being a pillaging enemy of the kingdom. There were plenty of Janzacs who laughed in that manner.

‘Are you one of the Golden Janzacs?’ Olivanin asked, eyeing his frayed travelling cloak.

‘Yes,’ Coran said. ‘I must apologise again, for I do not know who you are …’

She smiled. ‘I am the praetor’s daughter,’ she said.

Coran’s throat went dry. ‘Ah, it is an honour to meet you,’ he said, though by his tone, one might have thought it was more of a terror than an honour.

Olivanin continued to smile, though, as she arranged her exquisite, sapphire-blue dress in her lap. She nodded to the door on the work table by their side. ‘What’s the plan for the door, if you don’t mind me asking?’

‘Not at all,’ Coran said, turning to his project. After collecting his thoughts for a moment, he began detailing what he would be working on for the next few days before describing his vision for the finished creation.

Over the next little while, Olivanin came to the leatherworker’s store every day for a few hours. She often read or journaled, looking up when the regularity of Coran’s movements changed or when he was carving a particularly intricate section. Understandably, with her eyes over his shoulder, it was the best damn door Coran ever crafted.

CHAPTER ELEVEN: WORD IN THE CITY

Perhaps I should return now to those clever, courageous compatriots Toran left behind on the rock: chiefly, the sons of Rachrinor. We shall leave my parents to get to know each other for a little while. Nearly two years had passed since my uncle’s crew left Hazathsad, and tensions in the city there were at boiling point.

Word was everywhere in the streets that King Hamborty was planning a conquest. They were expecting that any day now, he would announce conscription. Dozens of war galleys were under construction in the main harbour.

There were rumours, also, that there was a sect within the Janzacs who opposed these operations. The small caravel that had left the island almost two years ago was said to be returning any day now to muster those who wished to join the cause.

Rachrinor guessed immediately that his sons were at the root of those roguish rumours, which meant Ravunbror and Rebror had gone completely underground—though not literally, thank goodness, for their father had not yet caught them. They were, in fact, hiding out in the very woods northwest of the city where the timber was milled for the galleys.

They kept the rumours circulating as best they could, faithfully holding onto the hope that they really were true.

Galorian had a rather important task as well, though none knew of it. If you have read the Balizon Bard’s account of Vonhoroth’s Final War, you will know that Galorian’s magpie was, in fact, a way for him to communicate with a wizard of great renown. Hearing of the situation on Hazathsad, the wizard had recognised instantly that there was one further thing that had to be done for there to be any hope of success for Toran’s plan.

You see, Vonhoroth manipulated King Hamborty through an Inferue, a shape-shifting spy who was disguised as the man’s wife. The wizard gave Galorian the task of assassinating that monstrous abomination. It was a difficult infiltration, as the queen spent most of her time in her rooms in the citadel, well away from the public eye and from the word in the city.

CHAPTER TWELVE: THE REQUEST

There came a time, in the unofficial courtship of Olivanin and Coran, when the Praetor of Iantal discovered just what sort of man his daughter was seeing every day. After his initial reaction of panic, rage and despair, he took a few deep breaths of the cool air drifting into the Great Hall in Iantal’s Spire and sat back down at the dining table across from Olivanin.

One of the servants near the table, waiting to take their plates, was looking pointedly away from the out-of-sorts praetor. He was staring up at the painted ceiling, which, at that time of year, perfectly depicted the night sky beyond it.

‘You’re telling me, Liv,’ he said in an exasperated tone, ‘that this carpenter you’ve been telling me so much about is a Janzac?’

‘Indeed, he is,’ said she, her eyes like tempered steel. ‘Had you not wondered why I didn’t mention his family?’

The praetor sighed. ‘I did guess that he must be low-born,’ he answered, ‘but strange marriages are not so uncommon for Iantalian nobles. My great-great-great-grandfather married an elf, which was beyond strange … but a Janzac?’

‘You must believe what I’ve told you of his character, Father,’ she said. ‘He denounces the evil ways of his people.’

‘Yes, I’ve read one or two of those pamphlets they sneak into the city,’ said the praetor. ‘I know what they say …’

‘You think he’s manipulating me? Lying?’ Olivanin asked.

‘I find the notion difficult to dismiss.’

‘I understand,’ Olivanin said slowly, ‘but I do not find it difficult to dismiss. I find it quite easy, for I have now spent many hours in conversation with the man.’

‘All the more time he’s had to dupe you.’

‘All the more time I’ve had to test him.’

Again, the praetor sighed. While he was quite worried, he also knew that his daughter was exceedingly clever and a rather excellent judge of character. At last, he said, ‘Well, I shall have to test him in conversation, myself. You shall invite him to dinner?’

A little shocked at her father’s sudden change of heart, Olivanin almost laughed. ‘Of course,’ she said.

By now, Coran had nearly completed the leatherworker’s door. The stained glass was set, and the wood—intricately carved on one side and left plain on the other to highlight the beauty of the various dark colours in the plum—was oiled many times over. In fact, he was working on the grooves for the hinges themselves when Olivanin arrived the following day to invite him to dinner.

Their conversation took him by surprise, of course. At first, he didn’t think it was such a good idea. He was sure that there were countless rulers across the islands of Durnam who would jump at the chance to publicly execute a Janzac. But, as Olivanin remarked, the praetor knew where Coran was staying and could have sent his soldiers to arrest him rather than his daughter to invite him to dinner. Thus, she convinced Coran that it was a peaceful gesture.

When Olivanin had left again, he began to realise just how important the dinner with the praetor was going to be. If he played his cards right—and had a miracle on the side—he might be able to get the praetor to send one of Toran’s pamphlets to Namrinor, to the High King himself …

No. What his crew really needed was a ship. They needed to get back to Hazathsad to help Ravunbror and Rebror, and to brave Whiterock Sea, they needed a ship of Janzac make that was small enough for them to man on their own. They needed one specific ship: the caravel Toran and Rador had built—and which had been burned by the Geremorians.

Coran, carried away by his own thoughts, worked long into the shadowy hours of night by the light of a few lamps. As he planned his words, he finished the grooves for the hinges and, in a kind of stupor, he removed the old, hip-high door.

A fresh breeze with the faint scent of approaching rainfall rushed at him as he straightened from this task. His eyes widened, and he took a deep breath as he woke himself up somewhat. He set the half-door aside as he looked at the empty frame he had created. He supposed that he needed to set the new door in place now—as he couldn’t very well leave the shop open to the night.

He went to bed in the thin hours before dawn, the Iantal job complete.

It so happened that the praetor decided, that morning, to go for a walk in the city. His chief purpose was to catch a glimpse of the Janzac carpenter who had seemingly ensnared his daughter. Coran, however, was very much asleep when the praetor called from the door.

Coran woke to Brenton shaking his shoulder violently.

‘The praetor is calling for you, lad!’ the old leatherworker hissed.

‘What?’ said Coran, leaping out of bed as if he’d been jabbed by a spear. ‘Now? What time is it?’

‘I’ve just finished breakfast,’ replied the leatherworker. ‘You’re usually working by now. Why does he want to see you?’

‘I don’t know,’ said Coran. ‘I thought I wasn’t meeting him until dinner tonight.’

Coran raced downstairs, buttoning up his jacket and stumbling on the second-to-bottom stair, as he often did. He arrived in the store and saw a tall, thin man staring at the leatherworker’s new door, his fingers tracing the patterns Coran had carved there. He had taken his glove off one hand in order to do so.

He looked up as Coran neared.

‘You’re the carpenter?’ he asked.

Coran nodded.

The praetor turned back to the door, shaking his head slowly. Then, to Coran’s pure astonishment, the man swore. ‘It’s a goddam masterpiece,’ he said. ‘It’s the most beautiful door on this road—and this is the most beautiful road in Tinoyamen.’

Coran swallowed. ‘You think so, my lord?’

The praetor turned to him, the edges of his mouth curving slightly. ‘Don’t ask me to repeat myself,’ he reprimanded lightly. He folded his arms. ‘This,’ he said, nodding at the door, ‘is more proof to me of your character than any conversation we could have. This is Iantalian in its beauty, which means that you are Iantalian in your heart.’

For a moment, Coran could find no words to reply with. Finally, he said, ‘Thank you, my lord.’

‘This is a gift to Iantal,’ he said. ‘It is customary that a manufacturer of a masterpiece such as this is given a gift in return.’

‘A gift?’ Coran asked.

The praetor nodded. ‘Iantal shall give you a gift,’ he said. ‘I expect to hear your request tonight after dinner.’

Then he swept quickly onwards, further into the city, and disappeared from view. Not long after, Coran guessed that while the praetor may indeed have been impressed by the artistry of the door, the real test of the Janzac’s character would be found in the nature of the request he made. Every thought of Toran’s plan—and the Janzacs waiting on Hazathsad—fled before the notion that he might plead for Olivanin’s hand in marriage.

The leatherworker paid Coran that morning for his work.

‘Brenton,’ Coran said, offering some of the coins back, ‘could I ask a favour of you?’

Brenton raised an eyebrow in reply.

‘I need new clothes,’ Coran continued, ‘or, at least, better clothes for my dinner with the praetor tonight. The problem is that I don’t believe any tailors will let me into their store. Could I trouble you to pick out a new shirt and boots for me?’

Brenton looked slowly down at Coran’s leather shoes, which were pulling apart in every conceivable place. He smiled. ‘I shall give you boots of my own make,’ he said. He accepted a coin back. ‘And I shall find you a shirt.’

So it was that when Coran arrived for dinner with Olivanin and the praetor, he was wearing dress boots that Brenton had made and a deep blue shirt from a tailor down the road. The three of them sat and ate in silence, alone in the great hall but for the company of the servants filling their glasses.

Once they had finished eating, the praetor took his wine glass in his left hand, a quill in his right, and asked for a sheet of paper. Once it was before him, he wrote a few lines that Coran could not make out from his end of the table—though Olivanin’s expression reassured him that it was not a death warrant.

At last, the praetor looked up, quill poised, and asked, ‘Your request?’

Coran took a breath, squaring his shoulders as he met the praetor’s keen gaze.

‘A gift is a gift,’ he began, ‘and by its very nature requires nothing in return.’

The praetor frowned slightly, and a spot of ink dripped onto the parchment before him.

Before he said anything, though, Coran pushed on. ‘But my situation is very dire, and I shall speak plainly of it if it pleases you.’

The praetor nodded.

‘I am torn, for while your daughter has become very dear to me, it would be a selfish and futile thing to ask for her hand, for you would not give it to a Janzac. If I had a daughter, I would not let a Janzac within a mile of her …

‘My brother has a plan, though. If it succeeds, I will no longer be a Janzac, and I shall approach you without shame to ask for Olivanin’s hand. For my brother’s plan to succeed, we need a few miracles. One of these miracles you could give us.’

Coran took another breath. ‘A door is a small thing in the grandeur of this city,’ he said. ‘I’m afraid that, in my grim situation, I must ask for a favour far beyond its equal. My brother, my companions and I need to build a ship to cross Whiterock Sea and give the Janzacs there an opportunity for redemption. To do this, we need the use of a piece of land on the coast with access to timber. That, I believe, would be my request—if I felt like I had any right to make it.’

The praetor began to clean the nib of his quill, and Coran’s heart fell.

‘You have a strange way of speaking plainly,’ the man said, and the edges of his mouth were curving towards a smile. ‘Your plan is still vague to me. Please explain it fully, for I am sure that the number of miracles I can work for your cause is more than one.’

My father was never entirely certain of why the praetor decided to trust him. My mother always told me it was the elfish flavour of their blood. Elfin magic is an intuitive kind that handles ideas of redemption and fluidity of character far better than the methodical practices of alchemy and conjuring …

Or, perhaps, it was just a miracle.

(END OF THIRD INSTALMENT. CLICK HERE FOR THE FOURTH.)