Lúthien Beloved

Home-thirst in Tolkien's 'Ælfwine of England' and C S Lewis's 'Perelandra'.

There was a land called England, and it was an island of the West […] that land the Elves named Lúthien and do so yet.

[…]

Now amidmost of that island is there still a town that is aged among men, but its age among the Elves is greater far; and, for this is a book of the Lost Tales of Elfinesse, it shall be named in their tongue Kortirion, which the Gnomes [Noldor Elves] call Mindon Gwar [now called Warwick].

[…] the Men of the North, whom the fairies of the island called Forodwaith, but whom Men called other names [Vikings], came against Gwar in those days when they ravaged wellnigh all the land of Lúthien.

- J R R Tolkien (The Book of Lost Tales — Part Two); edited by Christopher Tolkien.

One of the most fascinating parts of Tolkien’s legendarium is his original framing for The Book of Lost Tales — framing which Christopher decided to remove for simplicity’s sake when he arranged and edited the Quenta Silmarillion. In Tolkien’s drafts of The Book of Lost Tales (especially the draft titled Ælfwine of England), we find a frame story that unifies Middle-Earth and early mediaeval Europe — complete with Valar, Elves, Anglo-Saxons, Vikings/Forodwaith, Franks, Vandals and Romans. It is a tale of longing and ‘home-thirst’ and — like almost all of his work — it is a part of his never-ending love letter to England.

The Three Lúthiens

The Lúthien most of Tolkien’s readers are aware of is of course Lúthien Tinúviel — Lúthien from Sindarin Elvish, meaning ‘Daughter of Flowers’. You may have read of her in the chapter Of Beren and Lúthien in The Silmarillion or in the poetical account that Aragorn gives the hobbits in The Fellowship of the Ring:

The leaves were long, the grass was green,

The hemlock-umbrels tall and fair,

And in the glade a light was seen

Of stars in shadow shimmering.

Tinúviel was dancing there

To music of a pipe unseen,

And light of stars was in her hair,

And in her raiment glimmering.

There Beren came from mountains cold

And lost he wandered under leaves,

And where the Elven-river rolled

He walked alone and sorrowing.

He peered between the hemlock-leaves

And saw in wonder flowers of gold

Upon her mantle and her sleeves,

And her hair like shadow following.And many know that on Tolkien’s gravestone, ‘Lúthien’ is engraved beneath his wife’s name and ‘Beren’ beneath his own.

In the tale of Ælfwine of England, Lúthien is the Elvish name for England contrived to be the root of the Anglicized ‘Luthany’ (as it is used in Francis Thompson’s poem, The Mistress of Vision1), meaning ‘friendship’, and referring to the friendship between Men and Elves that was enjoyed there for thousands of years — some account of which can be found in the tales of Middle-Earth recorded in The Red Book of Westmarch (The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings) and The Golden Book (The Quenta Silmarillion). The name may also have a connection to 'Lothian', which remains a place name in Scotland of uncertain origins.

The End of the Tales

In Tolkien’s notes and drafts concerning Ælfwine of England — and its earlier poetical forms, The Sorrowful City and The Song of Eriol — he seems to include not only the invasion of England by the Romans and the Vikings (gradually driving the Elves out of their beloved Lúthien) but also appears to make reference to Constantinople (under the Old English ‘Micelgeard’), ‘Ælfred of Wessex’ (Alfred the Great) and Charlemagne (‘that king of the Franks that was upon a time most mighty among men’), which places this tale as having occurred in the early medieval period.

This story is then the end of Tolkien’s legendarium chronologically, yet it is also one of the earliest stories that Tolkien attempted to recount (the poetical versions were written around 1916 and the narrative version sometime after 1920). The story lays out the entire premise and framing for The Book of Lost Tales.

A Summary of Ælfwine of England

This is a summary of one of the last drafts of Ælfwine of England that Tolkien wrote — with some inclusion of earlier notes of interest (mostly drawn from The Book of Lost Tales — Part Two: VI: The History of Eriol or Ælfwine and the End of the Tales). Feel free to skip this section if you're familiar with the story …

Ælfwine is born of Déor (Déor the Minstral is a figure of ancient English legend to whom is attributed a poem of 42 lines in the Exeter Book) and Éadgifu (a ‘maiden of the West’) in the town of Mindon Gwar (Warwick). Their home is sacked by Vikings (‘Men of the North, whom the fairies of the island called Forodwaith, but whom Men called other names’), and both parents are slain.

Ælfwine becomes a slave — ‘a thrall to the fierce lords of the Forodwaith’ — yet is sustained by a dream and a longing inherited from his mother (the ‘home-thirst’ of Elves — or, in some drafts, the ‘sea-longing’ of his forefather, Eärendil).

Ælfwine knew not and had never seen the sea, yet he heard its great voice speaking deeply in his heart, and its murmurous choirs sang ever in his secret ear between wake and sleep, that he was filled with longing.2

At ‘the threshold of manhood’, he escapes and travels southwest to ‘lands where the Lords of the Forodwaith had not come’.

There is something of a pause in the narrative at this point, and it is explained that there were in those days seven invasions of Lúthien — and at each one, more of the Elves departed west, sailing ‘to the setting sun’. The invasion of the ‘ancient Men of the South […] the Men whose lords sat in the city of power that Elves and Men have called Rûm [an earlier draft calls their city ‘Micelgeard’ instead, an Old English name for Constantinople]’ caused the greatest number of Elves to leave Lúthien — for the Men of the South ‘did not even believe [the Elves] existed’.

The final invasion is that of the ‘children of Ing’ when ‘they came back to their own’ — the character Tolkien calls ‘Ing, King of Luthany’ is likely inspired by the combination of an Old English Runic Poem3 and the Roman writers’ term Inguaeones for the Baltic maritime peoples from the whom the English came. There is a prophecy mentioned in some of Tolkien’s notes: that Ing, or the kin of Ing, would one day guide the Elves back to their beloved Lúthien, where they would reign and ‘replant there the magic trees’. Ælfwine, in some of Tolkien’s notes, is not only said to be of the ‘kin of Ing’ but also the father of Hengest and Horsa (the founders of England) and Heorrenda (a name which Tolkien sometimes attributed to the writer of Beowulf, and the name of the bard who supplants Déor in the poem in the Exeter Book — meaning that in Tolkien’s early notes on his legendarium, Déor the Minstral seems to be supplanted by his grandson).

From this point, the tale of Ælfwine of England concerns itself with his attempt to sail westward until he satisfies the Elvish ‘home-thirst’ inherited from his mother; until he finds:

the kingdom of the Gods — even the aged Bay of Faëry […] Valinor, that is God-home.

When the first stage of his voyage ends in a shipwreck on an unknown island, he befriends the Valar (or archangel), Ulmo, Lord of Waters, there — who calls himself ‘the Man of the Sea’. Ulmo saves a different ship — made by the Men of the North (Vikings) — from the ‘Hungry Sands’ of the island for Ælfwine to use, and Ælfwine discovers that one of its deceased crew (who had all perished of thirst and hunger) was the very Northman who slew his father and enslaved him as a child.

In this ship, he makes it to a ‘land but little known’ where dwell the Ythlings, the ‘Children of the Waves’ whom the Elves call ‘the Shipmen of the West’. The Ythlings know Ulmo, and at his bidding, they fashion a new ship from ‘magic oaks far inland that grew about a high place of the Gods, sacred to Ulmo’. Ulmo then speaks words of magic over the ship, giving her ‘power to cleave uncloven waters and enter unentered harbours’. The Valar then departs, and Ælfwine sets sail again.

This particular draft ends two pages later with Ælfwine flinging himself from the ship and attempting to swim to the Lonely Isle, which is just short of the Undying Lands. Christopher Tolkien comments that it seems likely that this draft was to be the beginning of a complete rewriting of The Book of Lost Tales.

In separate notes written earlier, Tolkien describes Ælfwine waking on a sandy beach of the Lonely Isle, meeting the Elves and being brought to the Cottage of Lost Play. He begs them to return to England. They show him The Golden Book (The Quenta Silmarillion), and he begins to write The Book of Lost Tales4, a record of the stories of the Eldar Days and the explanation of why they cannot (yet) return.

Longing for Lúthien

Little of this story is canonised in Tolkien’s legendarium. It is a tale composed of some of his earliest scattered notes and drafts of his myth-making. Though there still remained some references to Ælfwine in Tolkien’s final drafts of The Silmarillion, Christopher Tolkien chose to remove them for simplicity’s sake. I think, though, that this character inhabiting the invisible frame of The Lost Tales is a very important lynchpin connecting Middle-Earth to the Middle Ages; bringing to the forefront of the tale, Tolkien's own longing for an England of Old; an Elven England; Lúthien.

When the Elves go to the Undying Lands (according to his notes regarding this tale), they begin naming places after the beloved landmarks and cities of their old home. Weary of the many wars and invasions of their Lúthien, they set sail to white shores, not longing for a wholly new land, only a new England that might not die the many deaths that the old England did — an undying Lúthien.

The ‘Home-Thirst’ of Ælfwine and Elwin

Ælfwine is Old English or Anglo-Saxon for ‘elf-friend’.

Regarding another Ælfwine (of the modern ‘Elwin’ variation) — the protagonist of C S Lewis’s Ransom Trilogy — Lewis wrote: ‘the hero (who is, by the way, to some extent a fancy portrait of a man I know, but not of me)’5. This, considered alongside the meaning of Elwin’s name and the fact that he is a philologist, draws many readers (myself included) to the conclusion that Dr Ransom was ‘to some extent’ based on Tolkien.

While voyaging in Venus (in Perelandra — the second book in the Ransom Trilogy), Elwin experiences a homesickness quite similar to the longing or ‘home-thirst’ that drives Ælfwine of England to search for the Undying Lands.

He would know it henceforth out of the whole universe — the night breath of a floating island in the star Venus. It was strange to be filled with homesickness for places where his sojourn had been so brief and which were, by any objective standard, so alien to all our race. Or were they? The cord of longing which drew him to the invisible isle seemed to him at that moment to have been fastened long, long before his coming to Perelandra, long before the earliest times that memory could recover in his childhood, before his birth, before the birth of man himself, before the origins of time. It was sharp, sweet, wild and holy, all in one […]

- C S Lewis (Perelandra)

These floating islands of Perelandra are rather obviously undying lands in that they are floating gardens of paradise, always moving — just as the Lonely Isle that Ælfwine reaches was also a floating island in the distant past. They do not fall still or become fixed — in fact, the one ‘fixed land’ on the planet is the equivalent of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (and thus a symbol of dying). I think that ‘to some extent’ Lewis was writing here of his good friend ‘Tollers’ discovering his Lúthien, the country which fulfilled his ‘home-thirst’.

Furthermore, in the next book — That Hideous Strength — Lewis writes that Arthur Pendragon (from whom Elwin Ransom is descended) is ‘In the Third Heaven, Perelandra. In Aphallin [likely a fictitious variation of ‘Avalon’], the distant island which Tor and Tinidril [the Adam and Eve of Perelandra] will not find for a hundred centuries’. Arthur Pendragon is a true English legend gone to his rest in the undying Lúthien.

The Where and When of Lúthien

This intertextuality is not a coincidence, of course. In the mid-1930s, Lewis and Tolkien made an agreement6: Lewis would write tales of space travel and Tolkien would write tales of time travel7.

Elwin takes a spaceship (shaped like a coffin) through the 'space' of the heavens to Perelandra; Ælfwine takes a Norse ship (the coffin of the Viking who enslaved him) across the seas of sunset and death to the Undying Lands of Faerie, which the Elves have built to mirror an England of long ago. Both of them journey to that specific time and place of our ‘home-thirst’, of our hearts’ true desire, which we love and long for — Eden, which was, and the Heavenly Jerusalem, which will be the meeting of the New Heaven and the New Earth; Venus, the morning and the evening star8.

The Lúthien that Lingers

Wandering around some of the north-western parts of Europe over the last little while, I've found myself stopping now and then to wonder about that lingering, fading shadow of Lúthien or Logres that Tolkien and Lewis strove to keep alive — campers stoking a dying fire as the cold of the postmodern world closed in.

I don't know much about my direct ancestors, really. From England and Scotland mostly, sure, but I don't know any specific places where they walked, places where they built houses of stone and wood, places where they lit fires to boil water for tea, sear a side of lamb and set out dough to rise, places where they taught their children how to hunt and mend their clothes, places where they spoke their final farewells to the Elves they'd lived alongside for so long.

Did they walk the same Roman roads as I — to Holy Island to seek healing from Saint Cuthbert? Did they build homes near Warwick, Cessford Castle or Craigellachie? Did they hunt in the same woods of birch and oak as the Elves?

Sometimes you can feel the longing of a place that has struggled to let go of its Lúthien nature. A lingering shadow, a wild edge, an old beauty glimmers across the landscape. The longing of an old stone that remembers still the touch of the Elves who once held it. The pride of an ancient tree planted by an Elf, which treasures still the place where Elven fingers trailed across its bark for the final time on their way into the west.

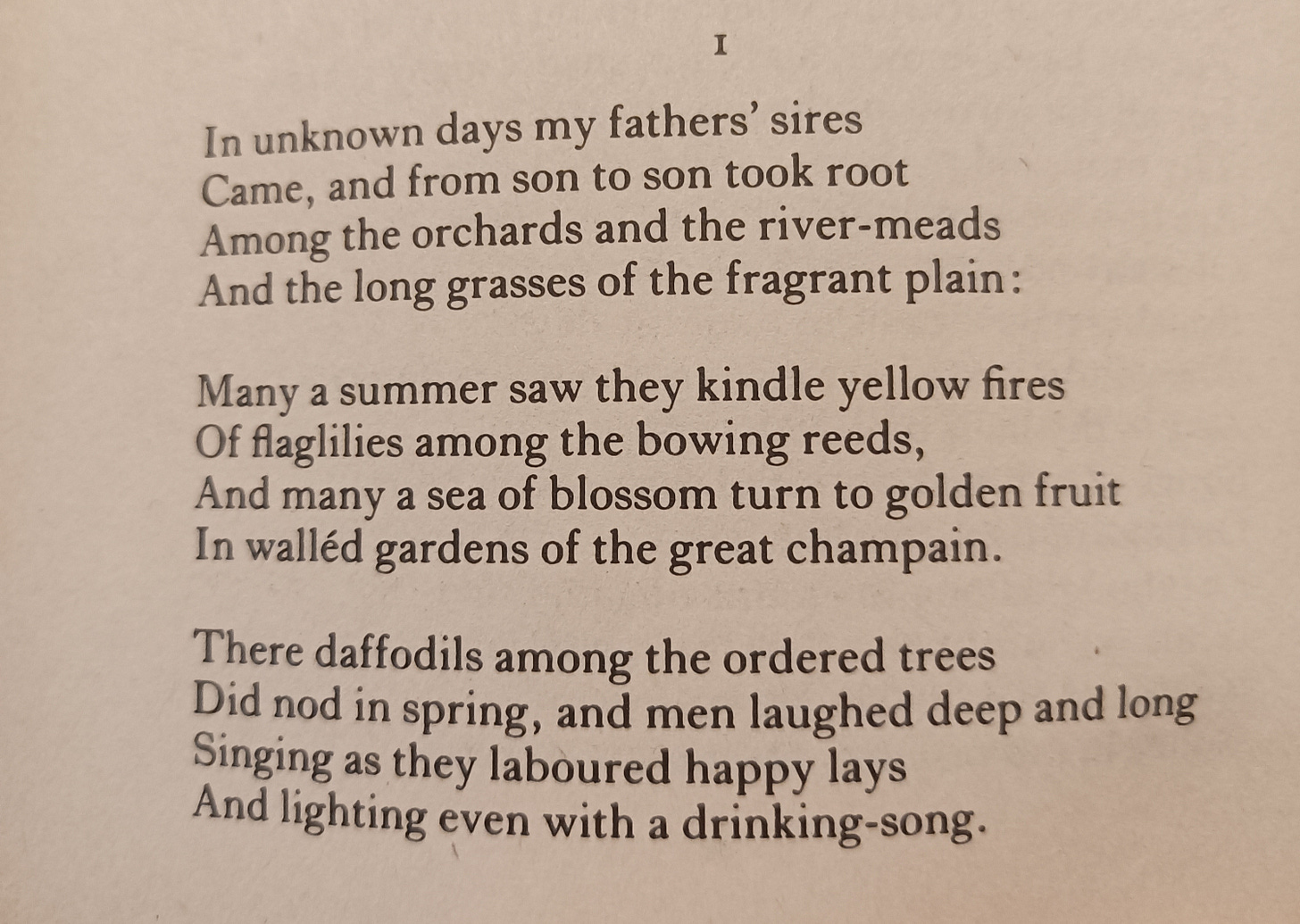

PS. The Song of Eriol

I often find the heart of Tolkien’s work in his verse. This tale of homesickness for Lúthien begins poignantly in these stanzas from The Song of Eriol — one of the earliest drafts of Tolkien's legendarium:

PPS. Warwick and The Sundering Sea

Also, I recently wrote two poems reflecting on these things: Warwick (I) and The Sundering Sea (II).

I. We woke to softly falling snow; Little of its magic had we known. We went by rail through countryside, Northwards through an England painted white. A castle there we sought to see, Built where once the Noldor, young and free, Had sung and called it Mindon Gwar -- Warwick now, where elves no longer are. Yet in the magic of the snow, Falling flakes which often seek to show A world imbued with every hue, Cased in white, is briefly more than true. Just briefly then, we trembling saw: Elven England, blistering, cold, no more. II. To gaze upon that western sea; To wish for roads that used to be Straight until the setting sun, But bent each time that Britain won. The long and loathsome war goes on; Though many battles have gone wrong, Logres endures in Númenórean hearts, As, in faith, their souls depart Along the bent but hallowed road To Venus, where they lay their load. Undying islands, welcome them, And keep them safely in our ken Until the days of their return, Until the rings of Saturn burn.

From Francis Thompson’s The Mistress of Vision:

The Lady of fair weeping,

At the garden's core,

Sang a song of sweet and sore

And the after-sleeping;

In the land of Luthany, and the tracts of Elenore.

The Book of Lost Tales — Part Two: VI: The History of Eriol or Ælfwine and the End of the Tales (J R R Tolkien; edited by Christopher Tolkien).

The Old English Runic Poem (translated): ‘Ing was first seen by men among the East Danes, until he departed eastwards over the waves; his car sped after him.’

In some versions, his son Heorrenda writes The Book of Lost Tales.

C S Lewis (A Reply to Professor Haldane).

Some evidence of this can be found in The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien; edited by Humphrey Carpenter.

While this does mean that the agreement was probably struck after Tolkien had written the draft of Ælfwine of England summarised above, I believe some of the impetus behind the agreement may have come from the time-travelling themes already evident in this part of Tolkien’s legendarium. Also, while The Lost Road is a later, more explicit attempt at a story of time travel into Middle-Earth, I do think Ælfwine of England is attempting a similar thing.

Aragorn and Arwen are also called the Morning Star and the Evening Star. They are the Beren and Lúthien of Middle-Earth's Third Age, and they are joined by names for Lúthien — the names for Venus and Elven England. This is part of why it makes sense for Arwen to give up the Undying Lands to be with Aragorn — he is her Morning Star, her Lúthien, and there would be no morning in the Undying Lands without him; Heaven and Earth could not be made new for her without him.

I loved this exploration, Peter; thanks so much for sharing it. Tolkien nut that I am, there was a lot here I wasn’t aware of. I love Deor—it’s one of my favorite Old English poems. That’s an interesting and entirely plausible proposition about the poet’s grandson.

It’s staggering to think what we’ve lost of that other world, but I think we’re beginning to see that modernity never replaced it; it was just built on top. The roots and the bedrock remain.

Very interesting! A lot of information I never read before! Thank you!