On the Way to the Beginning: Invisible Frames

Contemplating one of the most important literary poses in speculative fiction.

Thank you for joining me again in my musings on the way to the beginning. Though none of the other posts from the series are necessary preliminary reading, I’ll link them here in case you’re interested:

I should also note that the length of this post may be somewhat misleading. The quoted passages within the postscript and footnotes make up about half of it — and were only added on the off-chance that readers might want a deeper dive into some of the texts I revisited when I was writing this. My own contemplations will not take very long to express.

Fundamental to Tolkien’s method in The Lord of the Rings is a standard literary pose which he assumes in the Prologue and never thereafter relinquishes even in the Appendices: that he did not himself invent the subject matter of the epic but is only a modern scholar who is compliling, editing, and eventually translating copies of very ancient records of Middle-earth which have come into his hands, he does not say how.

- Paul Kocher (Master of Middle-Earth: the achievement of J. R. R. Tolkien)

Of old, true storytellers have not desired passively entertained listeners, watchers or readers of their craft. They have desired participants who will take up the challenges of the tales in their lives — just as their kinsmen in the tales did.

Of old, storytellers sought to obscure the frame between Audience and Art.

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Frankenstein

Of more recent times (the early Romantic era), Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. It is a framed tale. In the ballad, a mariner is halting a wedding guest to tell him a story. The salient narrative is this story The Mariner is telling, and The Mariner and The Wedding-Guest are, therefore, in the frame, and the frame is clearly defined — and you are outside it.1

This kind of framing is useful in creating a sense of being drawn deeper and deeper through layers of narrative — making the salient narrative feel all the more immediate and alive. There is another kind of framing, though — one that is less defined and pulls the reader yet deeper.

Mary Shelly began Frankenstein with four letters, which morph into the first chapter of the story — framing it in a different way — like this:

LETTER 1

To Mrs. Saville, England

(ST. PETERSBURGH, DEC. 11TH, 17—.)

You will rejoice to hear that no disaster has accompanied the commencement of an enterprise which you have regarded with such evil forebodings. I arrived here yesterday; and […]

LETTER 4

[…] This manuscript will doubtless afford you the greatest pleasure; but to me, who knew him, and who hear it from his own lips, with what interest and sympathy shall I read it in some future day! Even now, as I commence my task, his full-toned voice swells in my ears; his lustrous eyes dwell on me with all their melancholy sweetness; I see his thin hand raised in animations, while the lineaments of his face are irradiated by the soul within. Strange and harrowing must be his story; frightful the storm which embraced the gallant vessel on its course, and wrecked it—thus!

CHAPTER 1

I am by birth a Genevese; and my family is one of the most distinguished of that republic […]

You are reading a series of letters that gradually morph into a manuscript. The letters are written to ‘you’. The letters are the frame for the narrative, and you are in them — in other words, you are not outside the frame. The frame could well be reality — and the manuscript a forgotten record stumbled upon in the ruins of an old library. You might not be reading some fanciful, made-up tale; you just might be connected to it; participating in it.2

The frame between the art and your breathing body is almost invisible.

The Red Book of Westmarch

In the Modern era, Tolkien completed his translation of ‘The Red Book of Westmarch’ — in which Bilbo wrote There and Back Again, and Frodo and Sam wrote The Downfall of the Lord of the Rings and the Return of the King. (Did you notice that I’ve removed the frame already by saying the hobbits wrote it, not Tolkien? In these books, Tolkien does the same.)

It begins:

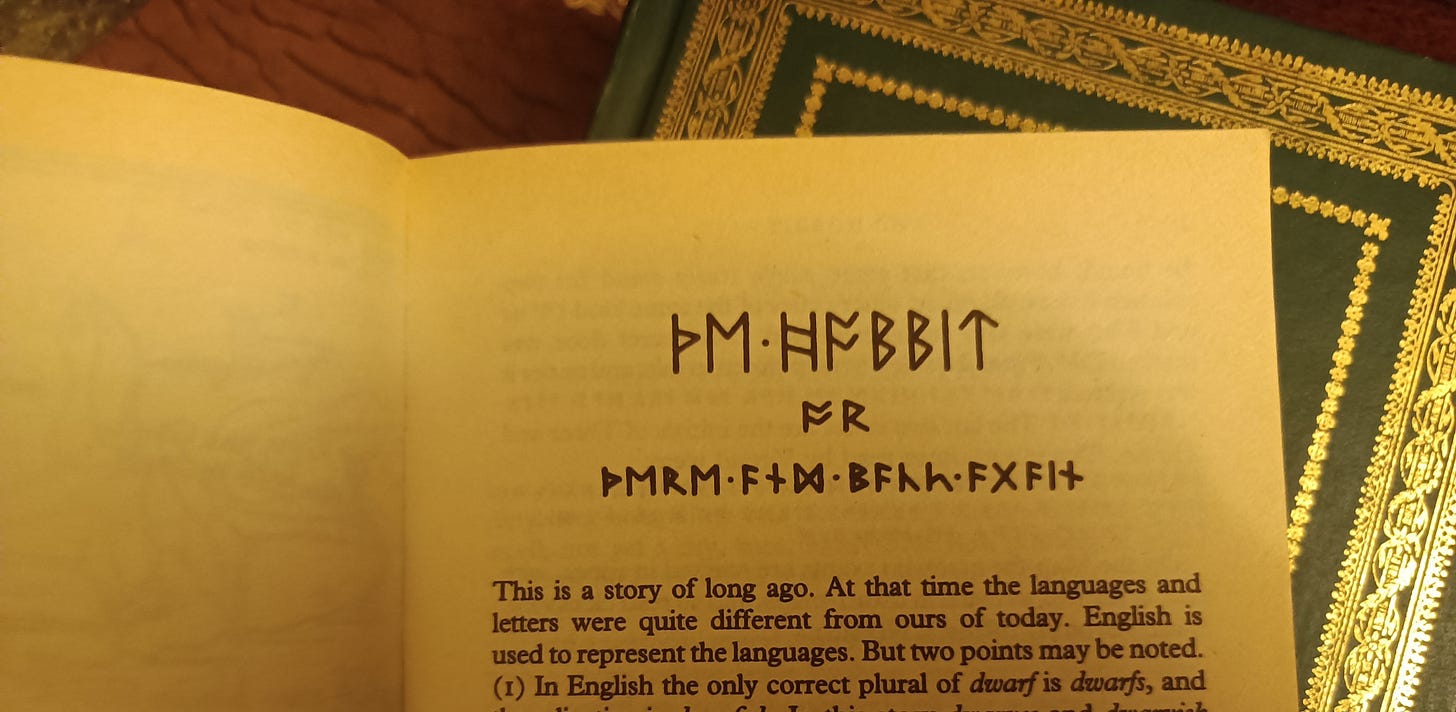

[Translated:] THE HOBBIT or THERE AND BACK AGAIN

This is a story of long ago. At that time, the language and letters were quite different from ours of today. English is used to represent the languages […]

And this (invisible) frame is reintroduced in the prologue to The Lord of the Rings, which reads:

PROLOGUE

1

Concerning Hobbits

This book is largely concerned with Hobbits, and from its pages a reader may discover much of their character and a little of their history. Further information will also be found in the selection from the Red Book of Westmarch that has already been published, under the title of The Hobbit. That story was derived from the earlier chapter of the Red Book, composed by Bilbo himself, the first Hobbit to become famous in the world at large, and called by him There and Back Again, since they told of his journey into the East and his return: an adventure which later involved all the Hobbits in the great events of that Age that are here related.

[…]

Even in ancient days [Hobbits] were, as a rule, shy of ‘the Big Folk’, as they call us, and now they avoid us with dismay and are becoming hard to find. They are quick of hearing and sharp-eyed, and though they are inclined to be fat and do not hurry unnecessarily, they are nontheless nimble and deft in their movements.

[…]

It is plain indeed that in spite of later estrangement Hobbits are relatives of ours: far nearer to us than Elves, or even than Dwarves. Of old they spoke the languages of Men, after their own fashion, and like and disliked much the same things as Men did.

So, you’re reading a book, and the author begins by explaining to a modern reader (you) that the book has been translated from an ancient language. Once again, you’re right there in the frame with the protagonists, recorders and translators of the events of the epic. Once again, you are participating in the story.

With this style of (invisible) framing, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Tolkien’s The Red Book of Westmarch proceed in the legacy of the most ancient and supreme folktales, mythologies and histories. Tolkien was especially aware of this — he famously implied that his writings about Middle-earth might be considered a mythology for the English (evidenced in some part by his assertion in the previous extract that ‘Hobbits are relatives of ours’, and expanded upon in the first chapter of Paul Kocher’s Master of Middle-Earth)3.

Further Thoughts on Participation in Secondary (or ‘Shadow’) Worlds

You don’t have to look far to find folk desiring to participate in stories — stories of the speculative kind in particular. Nearly everyone knows of at least a friend of a friend who enjoys the odd weekend of re-enacting battles from fantasy novels in a Live Action Role-Playing setting. Nearly everyone also knows of folk who have named their pets or even children after their favourite authors or after characters from their stories.

[…] Tolkien knew, none better, that no audience can long feel sympathy or interest for persons or things in which they cannot recognize a good deal of themselves and the world of their everyday experience. He therefore added that a secondary world must be “credible, commanding Secondary Belief.”

- Paul Kocher (Master of Middle-Earth)

In more religious terms, the secondary worlds created in speculative fiction give testimony to God’s image within us. Just as Creation is a shadow of God’s reality, so we create ‘shadow’ worlds. God is the light that reveals reality — the ‘I AM’ — and Creation is the object that reflects the light and casts the shadows; therefore, these shadows always point homeward in some way, regardless of our intentions. And, of course, God Himself delights in participating in His own creation; it makes sense that we should wish to do the same with our ‘shadow’ worlds.

The stories most participated in throughout history are undoubtedly mythologies and religious texts.

Mythology is not a disease at all, though it may like all human things become diseased. You might as well say that thinking is a disease of the mind. […] The incarnate mind, the tongue, and the tale are in our world coeval.4

- J R R Tolkien (On Fairy-Stories)

Contemplation, language and storytelling developed in synchrony; participation in any one of them provoked participation in the others.

No story has provoked as much participation (in contemplation, language and action) as that of Christ — and all ‘shadow’ worlds are, in the final analysis, shadows of Him and of home. Following the shadows, we exiles wander through imperfect frames and fractured participation, seeking to delve ever deeper into the truest stories we can find.

Returning to the Invisible Frame

As a literary pose or device, framing is exceptionally useful in drawing the audience deeper into the story. Some storytellers — especially mythologists — understand that the deepest engagement between audience and art is born when the frame becomes (invisible) reality. Tolkien, with The Red Book of Westmarch in particular, seemed to see clearly this mission to obscure the frame between Fantasy and reality — the mission to encourage exiles to participate in the ‘shadow worlds’ that point us towards our home.

~

Peter Harrison

PS. Flames of the Exiled and Of Ashes Born

I am attempting to form just such an obscure frame for Flames of the Exiled and Of Ashes Born. The structure of the former is quite similar to Frankenstein — a manuscript framed by a number of notes written directly to the intended recipient of the story — and the latter novella is structured as an addendum written by a different storyteller.

The current draft of Flames of the Exiled begins like this:

NOTE: THE STORY ENCLOSED

To His Imperial Highness Prince Zündenai, heir to the throne of the empire,

Peace be with you as you contemplate the many choices you must make that will define our future.

I visited your palace once. Such a majestic spectacle is difficult to forget. As I took in the soaring turrets and menacing wall-mounted trebuchets, I pictured that most famous siege which first spread your uncle’s name to every corner of Durnam. I pictured your beautiful, sprawling castle in flames, the marauding savages gathering behind the battlements to see your uncle’s army returning to reclaim their capital.

Your uncle razed his own castle to the ground in order to purge it of enemies.

His legacy is one of extreme tactical prowess, fire-tempered discipline and justice unbent by mercy. As you endeavour to build on this legacy, I beg you to grant me your attention for just a little while. Hear this story—my gift to Your Imperial Highness, to help you make sense of this recent chaos, the rise of your empire and the exile of the Taranor […]

And the novella (Of Ashes Born) begins like this:

PRELUDE TO OF ASHES BORN: MY UNCLE’S STORY

Whitewater rises here in raucous froths and spurts as if heaven itself is filling the sea with its jubilance.

If you had been here thirty-four years ago, however, you would have been told that this ocean was a spring straight from the broken stone of hell—and you would have been told that this island, Hazathsad, was the shattered stone itself. That is what my father told me. That is how he always began this story.

I don’t know how many times he told me this tale before my mother suggested I write it down. After I decided to take her advice—by which time she had passed on—my father repeated the history to me many times more.

My first retelling of this story—a story which I myself had no part in—was at my father’s funeral. I stood at the lords’ dining table beside my younger brother and read a summary of it from this very book I am writing in—as I sit here, on Mount Hronver, and watch Whiterock Sea.

I have read the Balizon Bard’s account of Vonhoroth’s Final War—his exoneration of my people—and I believe that this may be an informative seventh book to that story. It is a prequel, a story not of our generation but of our fathers’. It is the story of how my people abandoned this island and this ocean. You can read the bard’s account to learn of our return.

So, my father always began by telling me that Whiterock Sea was a Hellspring from Hazathsad, the broken stone of Cthartarus itself. The second thing he always told me was this:

‘My brother was the leader—the hero. For the most part, this is your uncle’s story; not mine.’

PART ONE: THE JANZACS OF HAZATHSAD

CHAPTER ONE: THE JANZAC WHO DREAMED

My uncle’s name was Toran Tarrathonson. Like most Janzacs, he referred to Hazathsad as ‘the rock’, and the stormy skies above, he called the ‘hells’ rather than the ‘heavens’ […]

PPS. The novella is currently free to read here on Substack — along with the beginning of Flames of the Exiled.

The beginning of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner:

It is an ancient Mariner, And he stoppeth one of three. 'By thy long grey beard and glittering eye, Now wherefore stopp'st thou me? The Bridegroom's doors are opened wide, And I am next of kin; The guests are met, the feast is set: May'st hear the merry din.' He holds him with his skinny hand, 'There was a ship,' quoth he. 'Hold off! unhand me, grey-beard loon!' Eftsoons his hand dropt he. He holds him with his glittering eye— The Wedding-Guest stood still, And listens like a three years' child: The Mariner hath his will. The Wedding-Guest sat on a stone: He cannot choose but hear; And thus spake on that ancient man, The bright-eyed Mariner. 'The ship was cheered, the harbour cleared, Merrily did we drop Below the kirk, below the hill, Below the lighthouse top.

Patrick Rothfuss’s The Kingkiller Chronicles are like the The Rime of the Ancient Mariner in their framing:

PROLOGUE

A Silence of Three Parts

It was night again. The Waystone Inn lay in silence, and it was a silence of three parts.

[… several chapters later …]

“I know your reputation as a great collecter of stories and recorder of events.” Kvothe’s eyes became hard as flint, sharp as broken glass. “That said, do not presume to change a word of what I say. If I seem to wander, if I seem to stray, remember that true stoies seldom take the straightest way.”

[…]

Kvothe gave a gentle smile and looked around the room as if fixing it in his memory. Chronicler dipped his pen and Kvothe looked down at his folded hands for as long as it takes to draw three deep breaths.

Then he began to speak.

“In some ways, it began when I heard her singing. Her voice twinning, mixing with my own […]”

Chronicler let slip a small laugh, though he did not not look up from his page or pause in his writing.

Kvothe continued, smiling himself. “I see you laugh. Very well, for simplicity’s sake, let us assume I am the centre of creation. In doing this, let us pass over innumerable boring stories: the rise and fall of empires, sagas of heroism, ballads of tragic love. Let us hurry forward to the only tale of any real importance.” His smile broadened. “Mine.”

~

My name is Kvothe, pronounced nearly the same as “Quothe”. Names are important as they tell you a great deal about a person. I’ve had more names than anyone has a right to […]

One little scene break symbol, and we have moved from frame into salient narrative. Similar to The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, you are reading a story; in the story, an innkeeper is narrating his story to a chronicler. They are in the frame, the frame is clearly defined and you are outside it.

In Dracula, Bram Stoker achieves a blurring of the frame similar to Mary Shelley in Frankenstein by telling the entire story through extracts from journals, diaries, newspapers and letters — beginning in this way:

CHAPTER 1

JONATHAN HARKER’S JOURNAL

(Kept in shorhand.)

3 May. Bistritz.—Left Munich at 8:35 P. M., on 1st May, arriving at Vienna early next morning; should have arrived at 6:46, but train was an hour late. Buda-Pesth seems a wonderful place, from the glimpse which I got of it from the train […]

Further commentary on the the framing of The Red Book of Westmarch can be found in the first chapter of Paul Kocher’s excellent work, Master of Middle-Earth: the achievement of J. R. R. Tolkien, in which he writes:

About the hobbits, for instance, the Prologue informs the reader that they are “relations of ours,” closer than elves or dwarves, though the exact nature of this blood kinship is lost in the mists of time. We and they have somehow become “estranged” since the Third Age, and they have dwindled in physical size since then. Most striking, however, is the news that “those days, the Third Age of Middle-earth, are now long past, and the shape of all lands has been changed; but the regions in which Hobbits then lived were doubtless the same as those in which they still linger: the North-West of the Old World, east of the Sea.”

There is much to digest here. The Middle-earth on which the hobbits lived is our Earth as it was long ago. Moreover, they are still here, and though they hide from us in their silent way, some of us have sometimes seen them and passed them on under other names into our folklore. Furthermore, the hobbits still live in the region they call the Shire, which turns out to be “the North-West of the Old World, east of the Sea.” This description can only mean northwestern Europe, however much changed in topography by eons of wind and wave.

The suggestion that participation in contemplation, language and storytelling developed in synchrony is followed by a few ideas regarding sub-creation and secondary worlds which I will quote here — as they are also relevant to the topic of narrative framing. (I have changed the paragraph structuring in this quote for easier digital reading.)

The human mind, endowed with the powers of generalization and abstraction, sees not only green-grass, discriminating it from other things (and finding it fair to look upon), but sees that it is green as well as being grass. But how powerful, how stimulating to the very faculty that produced it, was the invention of the adjective: no spell or incantation in Faerie is more potent. And that is not surprising: such incantations might indeed be said to be only another view of adjectives, a part of speech in a mythical grammar.

The mind that thought of light, heavy, grey, yellow, still, swift, also conceived of magic that would make heavy things light and able to fly, turn grey lead into yellow gold, and the still rock into a swift water. If it could do the one, it could do the other; it inevitably did both. When we can take green from grass, blue from heaven, and red from blood, we have already an enchanter’s power — upon one plane; and the desire to weild that power in the world external to our minds awakes.

It does not follow that we shall use that power well upon any plane. We may put a deadly green upon a man’s face and produce a horror; we may make the rare and terrible blue moon to shine; or we may cause woods to spring with silver leaves and rams to wear fleeces of gold, and put hot fire into the belly of the cold worm. But in such “fantasy,” as it is called, new form is made; Faerie begins; Man becomes a sub-creator.

An essential power of Faerie is thus the power of making immediately effective by the will the visions of “fantasy.” Not all are beautiful or even wholesome, not at any rate the fantasies of fallen Man. And he has stained the elves who have this power (in verity or fable) with his own stain. This aspect of “mythology” — sub-creation, rather than either representation or symbolic interpretation of the beauties and terrors of the world — is, I think, too little considered.