On the Way to the Beginning: Sermons and Speeches

What makes a story seem preachy or propagandistic, and is preachiness always bad?

A good novel tells us the truth about its hero; but a bad novel tells us the truth about its author.

- G K Chesterton (Heretics)

Do storytellers create the characters in their tales? Perhaps I should ask if sculptors create statues or gardeners create gardens … With these questions, I feel I am venturing into the twilit realm of co-creation.

You see, we are now trying to understand, and to separate into water-tight compartments, what exactly God does and what man does when God and man are working together. And, of course, we begin by thinking it is like two men working together, so that you could say, “He did this bit and I did that.” But this way of thinking breaks down. God is not like that. He is inside you as well as outside: even if we could understand who did what, I do not think human language could properly express it.

- C S Lewis (Mere Christianity)1

So, God within and encompassing, the gardener turns the soil and presses the seed into its keeping. The sculptor tinkers with the stone until it reveals its nature. Perhaps the storyteller should follow their example. They should plough the page with patience, press their characters’ names into the paper with curiosity and handle them lightly as they reveal themselves — abide in the manner of intentional friendship.

This instalment of the On the Way to the Beginning series reiterates and amalgamates elements from Pulling and Following a Story and The Dark Before Dawn; if you’d like to contemplate co-creation, creative play, believable characters and sermons within stories, I hope these explorative thoughts will be of some interest.

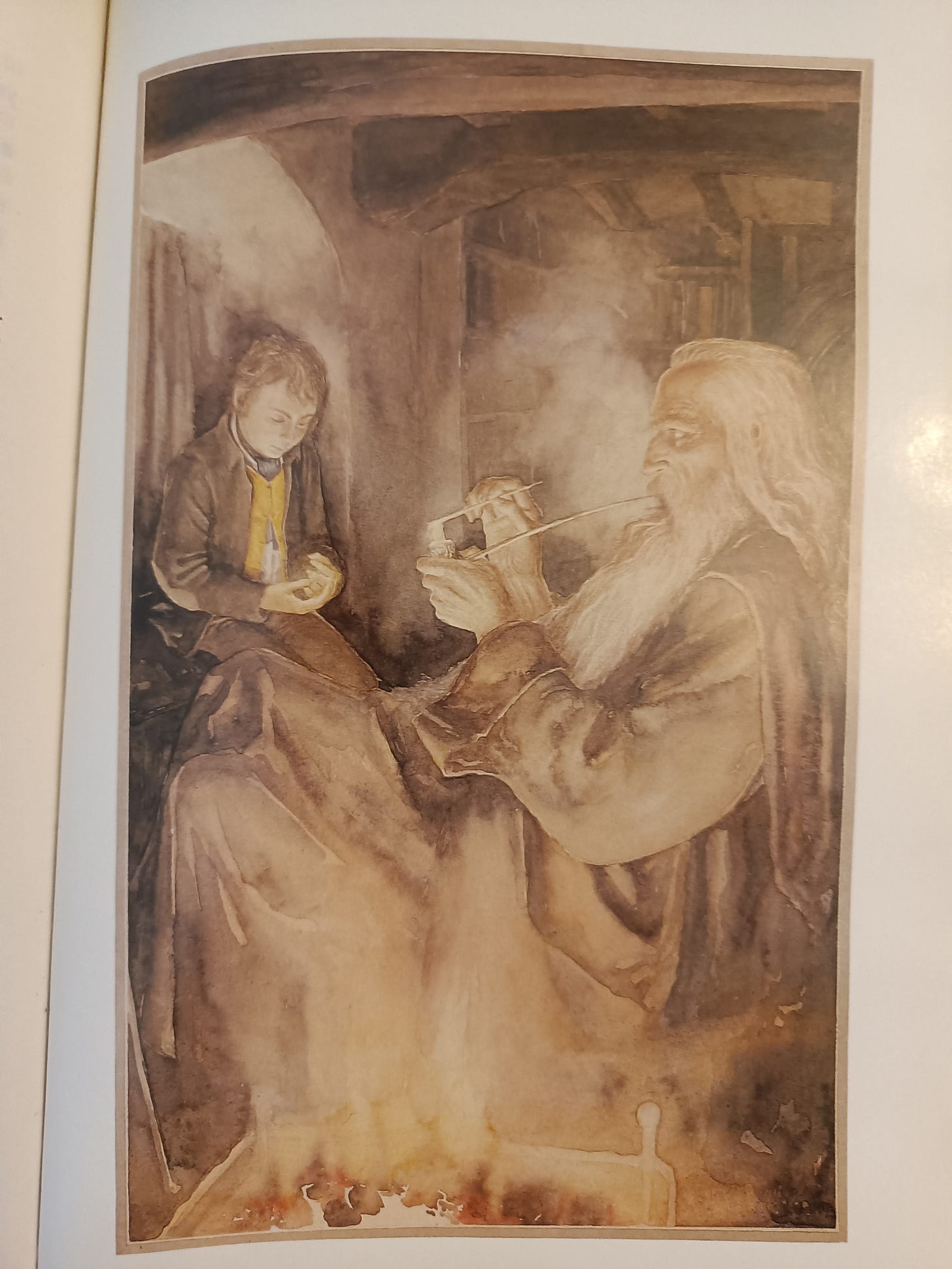

It is common to hear complaints about a book or a film being too preachy or propagandistic, but it is not often clear what exactly is meant by this. There are certain kinds of preachy storytelling I dislike, of course, but I do think that preachiness can also be (and often is) compelling — like when a priest delivers a sermon believable in the context of his character. I am thinking of some of the more vocal figures in the works of Dostoevsky2, Orwell3, Dickens, G K Chesterton, George MacDonald4, C S Lewis and J R R Tolkien. Consider this passage from the second chapter of The Fellowship of the Ring:

[Frodo:] ‘What a pity Bilbo did not stab that vile creature, when he had a chance!’

[Gandalf:] ‘Pity? It was pity that stayed his hand. Pity, and Mercy: not to strike without need. And he has been well rewarded, Frodo. Be sure that he took so little hurt from the evil, and escaped in the end, because he began his ownership of the Ring so. With pity.’

[…]

‘Many that live deserve death. And some that die deserve life. Can you give it to them? Then do not be too eager to deal out death in judgement. For even the very wise cannot see all ends.’

This dialogue from Gandalf could be considered preachy, but it also feels like just the kind of thing an angel or a wizard would say — and I think that could be the key to crafting stories with what might be considered an acceptable kind of preachiness: write believable characters. For, while we are much more likely to forgive an author for writing a sermon into a story if we agree with what they wrote, the acceptability of such speeches — beyond our agreement with them — does, I think, come down to a character’s believability.

In Pulling and Following a Story, I wrote about the role of a character’s decisions in cultivating engaging stories:

Stories where you seek to follow the character making interesting decisions will often grip you more than stories where the character is pulled along by the events of the plot. However, the choices the character faces are only interesting if they are meaningful, and they only mean something if they are attempting to map out — to plot — the symbols and patterns of reality.

And in The Dark Before Dawn, I contemplated the necessity of wise carelessness — which is, I think, especially important when it comes to writing believable characters:

[…] a creative project requires a paradoxical commitment to both getting it right and not caring if you succeed (necessitating an aspect of play in the process).

The term ‘passion project’ might be a helpful descriptor for those attempts at creation where the artist becomes too concerned with the seriousness of getting something right — much like a suitor or spouse too serious about getting romance right. The lack of play or wise carelessness renders an artist and a wooer impotent. This is probably because they have elevated their project too high while grasping it too firmly. They have cradled their seed in desperate worship instead of lowering it to be planted in the Father’s wisdom that He might raise it up according to His will […]

An idea for a character might enter our minds as a simple image, a string of formative circumstances or a single strong sentence a person might be prone to say. This seed will not take root in a story unless we relinquish our control of it — unless we resist the pride of self-creation and accept instead the human role of co-creator. There may arise a need to guide its growth with a trellis, transplantation, fertiliser or pruning — the introduction of an opposing or assisting character, the imposition of an exile, a catastrophe or a eucatastrophe — but the growing itself is best done out of sight; perhaps aided by prayer, music and sleep.

If you don’t befriend your characters — if you don’t let them reveal themselves to you through play — you may well be tempted to speak for them in the story (because you don’t know them well enough to write what they would really say), and that, I believe, is when a reader may begin to suspect an author is preaching at them. The fictional characters in our stories can behave like avatars, caricatures, archetypes, spirits or ideologues trying to control us as much as we’re trying to control them. If we do not befriend them, we may find ourselves possessed by the ideological inclination to deliver unwanted sermons to the folk we encounter through the stories we write and even to those we meet in our day-to-day lives.

The characters I might warn against befriending are, of course, those spirits who wander deep into the pits of villainy. Perhaps befriending is the wrong idea at this point (a note could be made here about the Jungian notion of integrating one’s shadow, but I have not read enough of Jung’s work to make it). I think the most we can do in the case of the deeply villainous is love them — the trust involved in friendship becomes dangerous at these depths.

I wish we could sometimes love the characters in real life as we love the characters in romances. There are a great many human souls whom we should accept more kindly, and even appreciate more clearly, if we simply thought of them as people in a story.

- G K Chesterton (What I Saw in America)

In your life and in your stories, you might befriend a priest or a politician who tends to sermonise in every conversation. I see two options here:

Be patient. Let them speak until they run out of breath — when writing a story, I’ve found it helpful to let such difficult characters dictate a monologue or dominate a dialogue for a while — and then maybe you can go on an adventure together. Their sermons and speeches may or may not make it into your account of the adventure, but they might just need to say them regardless.

Armour each priest and politician with everything you can and then let them have at it. This is obviously a more intellectually strenuous option, and one might benefit from spending a few thousand words trying to imitate writers like Orwell, Dostoevsky or Chesterton. It may seem insincere or unhelpful to suggest that one should simply try to imitate a few of the greatest authors of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, but I think that to learn any craft, the simple and almost unavoidable method is imitation; especially the imitation of the most compelling craftsmen we can find.

No storyteller is unbiased. No storyteller is able to completely wipe their worldview from their writing — nor should they attempt to — but I think a committed storyteller might eventually discover that the characters they handle lightly are less preachy than the ones they manipulate (or, the characters an author follows preach less than the ones they pull).

Thanks for reading; I hope these thoughts were of some interest. Please consider subscribing if you would like to see more of what I’m working on (fiction, poetry and thoughts), and do continue on to the postscript of this essay if you’re interested in a long tangent concerning propaganda.

~

Peter Harrison

~

PS. Concerning Propaganda

Reading Acts with a friend recently, we got into a great conversation about spells, art, speeches and propaganda. Some of the thoughts voiced might fit well as an addendum to this explorative essay. Here’s part of the salient passage:

But that it spread no further among the people [New Living Translation: ‘to keep them from spreading their propaganda any further’], let us [the rulers, elders and scribes of the temple] straitly threaten them [the Apostles Peter and John], that they speak henceforth to no man in this name.

Acts 4:17 (KJV)

We found the addition of the word ‘propaganda’ in the New Living Translation particularly thought-provoking. The Catholic Church coined the term in 1622 in the naming of their counter-reformation missionary organisation, Congregatio de Propaganda Fide (Congregation for Propagating the Faith). The word developed from the Latin propagare (meaning ‘to spread or propagate’), and it was not used to denote ‘the spreading of ideas or information of questionable accuracy as a means of advancing a cause’ until the beginning of the nineteenth century.

I think the chief effort of propaganda (in the modern sense of the word) is to spell something out for its audience so that they do not feel compelled to think deeply about it themselves. To spell something out is to cast a hubristic illusion of complete understanding, and such illusions get more dangerous the more important their subject is (which is part of why it is considered sacrilegious to spell out God’s name — it would be a prideful assertion that we had a complete understanding of Him).

Sermons and speeches are spells cast over multitudes of people anent subjects deemed important by the attention of their audience, which makes them quite dangerous. This is part of why the rulers, elders and scribes in this passage were so concerned about the Apostles Peter and John going out and casting the propaganda spell in their Rabbi’s name.

Oration can certainly be considered an art form in the original Latin sense of ‘fitting things together’ (it is used to fit an audience together with their purpose or telos by way of rhetoric and logos); so here we find one of the many meetings of art and propaganda — and a tricky question is posed:

What is the difference between the propaganda spell and the art spell?

Can an artist ever wipe the bias of their worldview from what they write and say? The Apostles didn’t seem to think so. They reply to the threat from the rulers, elders and scribes:

Whether it be right in the sight of God to hearken unto you more than unto God, judge ye. For we cannot but speak the things which we have seen and heard.

Acts 4:19-20 (KJV)

Does this make their oration propaganda? I think so — in the original sense of the word, at least. Characters are seeds propagated in the soil of a story. The moment a character enters a story or an object is characterised, that propagation attempts to take hold in the audience also — making all stories propaganda (again, in the original sense of the word).

The modern sense of the word, though, certainly diverges from art — or could be seen as a parasite corrupting art. I think that propaganda, in its modern sense, is the arrogant endeavour to pin down and present a half-truth or a lie, whereas art is based on the earnest, humble and open-handed pursuit of truth. Artists are fallible, though, and in their pursuit of truth, they may make assumptive errors that could be called accidental propaganda — half-truths and lies are far easier to find and pin down, after all.

How, then, might artists limit these kinds of errors? Ready for me to attempt to tie this tuba of a tangent back into an essay about co-creation and writing believable fictional characters?

It may be helpful to note that Christ uses riddles and parables prodigiously and gives answers infrequently. Christ often goes to great lengths to resist the spelling out of His teachings (and — for the first half of His ministry — His name). He tells stories that confuse people and then says:

He that hath ears to hear, let him hear.

Mark 4:9 (KJV)

That’s almost the opposite of spelling it out for an audience — it’s a call for the listeners to abide in a holy mystery. He holds the answers they desire but knows that knowledge grasped prematurely is never perceived accurately5. Perhaps, to avoid errors that look like accidental propaganda, we should avoid attempts to spell out, pin down or control our characters; let them reveal themselves as patient friends do — without a clear structure or premature judgement.

In this passage, C S Lewis contemplates the question of whether one is saved by faith or works, but I think his words also apply more generally to the idea of co-creation or working with God.

Part of a paragraph from Father Zossima’s last words in Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov:

And how much that is great, mysterious and unfathomable there is in it! Afterwards I heard the words of mockery and blame, proud words, “How could God give up the most loved of His saints for the diversion of the devil, take from him his children, smite him with sore boils so that he cleansed the corruption of his sores with a pot-sherd—and for no object except to boast to the devil! ‘See what My saint can suffer for My sake.’” But the greatness of it lies just in the fact that it is a mystery—that the passing earthly show and the eternal verity are brought together in it. In the face of the earthly truth, the eternal truth is accomplished. The Creator, just as on the first days of creations He ended each day with praise; “That is good that I have created,” looks upon Job and again praises His creation. And Job, praising the Lord, serves not only Him but all His creation for generations and generations, and for ever and ever, since for that he was ordained. Good heavens, what a book it is, and what lessons there are in it! What a book the Bible is, what a miracle, what strength is given with it to man! It is like a mold cast of the world and man and human nature, everything is there, and a law for everything for all the ages. And what mysteries are solved and revealed! God raises Job again, gives him wealth again. Many years pass by, and he has other children and loves them. But how could he love those new ones when those first children are no more, when he has lost them? Remembering them, how could he be fully happy with those new ones, however dear the new ones might be? But he could, he could. It’s the great mystery of human life that old grief passes gradually into quiet, tender joy. The mild serenity of age takes the place of the riotous blood of youth. I bless the rising sun each day, and, as before, my heart sings to meet it, but now I love even more its setting, its long slanting rays and the soft, tender, gentle memories that come with them, the dear images from the whole of my long, happy life—and over all the Divine Truth, softening, reconciling, forgiving! My life is ending, I know that well, but every day that is left me I feel how my earthly life is in touch with a new infinite, unknown, that approaching life, the nearness of which sets my soul quivering with rapture, my mind glowing and my heart weeping with joy.

A fragment from a sermon about The Party in Orwell’s 1984:

Now I will tell you the answer to my question. It is this. The Party seeks power entirely for its own sake. We are not interested in the good of others; we are interested solely in power, pure power. What pure power means you will understand presently. We are different from the oligarchies of the past in that we know what we are doing. All the others, even those who resembled ourselves, were cowards and hypocrites. The German Nazis and the Russian Communists came very close to us in their methods, but they never had the courage to recognize their own motives. They pretended, perhaps they even believed, that they had seized power unwillingly and for a limited time, and that just around the corner there lay a paradise where human beings would be free and equal. We are not like that. We know that no one ever seizes power with the intention of relinquishing it. Power is not a means; it is an end. One does not establish a dictatorship in order to safeguard a revolution; one makes the revolution in order to establish the dictatorship. The object of persecution is persecution. The object of torture is torture. The object of power is power. Now you begin to understand me.

A revelation from the narrator of George MacDonald’s Phantastes — imparted near the end of his travels:

Ere long, I learned that it was not myself, but only my shadow, that I had lost. I learned that it is better, a thousand-fold, for a proud man to fall and be humbled, than to hold up his head in his pride and fancied innocence. I learned that he that will be a hero, will barely be a man; that he that will be nothing but a doer of his work, is sure of his manhood. In nothing was my ideal lowered, or dimmed, or grown less precious; I only saw it too plainly, to set myself for a moment beside it. Indeed, my ideal soon became my life; whereas, formerly, my life had consisted in a vain attempt to behold, if not my ideal in myself, at least myself in my ideal.

This is from

’s excellent piece “The West Must Repent,” he blogged:When you bite into knowledge prematurely, you’re not perceiving it in its proper context.

You make so many good points in this piece. I was especially interested in your notes on propaganda and how Jesus calls “listeners to abide in a holy mystery.”

In the end it seems to me a simple matter. Preaching and being preached to are part of the human experience, and therefore an appropriate subject for fiction. The question is, in any particular case, does the preaching exist for the sake of the story, or was the story concocted as a vehicle for the preaching? Given reasonable storytelling skills, the former will not feel preachy, but the latter always will.