On the Way to the Beginning: Phantasy and Faërie

The seeds that are planted at night; the stories that grow while we sleep (feat. the forefathers of modern Fantasy, J R R Tolkien and George MacDonald, and the biblical symbologist, Matthieu Pageau).

Many of the essays in this series seem to involve quotes from Tolkien’s On Fairy-Stories. This essay is no exception, and the quote that follows is an extract from the text that I have often found confusing and thought-provoking; so, following the quote are a few explorative thoughts about the intersection of the Dream and Faërie.

(It is a rather long extract — about a page — but I must ask you to bear with me, as the quote serves as a necessary introduction to the essay that follows. Also, the paragraph structure has been altered in an attempt to make it easier to read in this electronic format and I have added my own emphasis in bold.)

I would also exclude, or rule out of order, any story that uses the machinery of the Dream, the dreaming of actual human sleep, to explain the apparent occurrence of its marvels. At the least, even if the reported dream was in other respects in itself a fairy-story, I would condemn the whole as gravely defective: like a good picture in a disfiguring frame.

It is true that Dream is not unconnected with Faërie. In dreams strange powers of the mind may be unlocked. In some of them a man may for a space wield the power of Faërie, that power which, even as it conceives the story, causes it to take living form and colour before the eyes. A real dream may indeed sometimes be a fairy-story of almost elvish ease and skill — while it is being dreamed. But if a waking writer tells you that his tale is only a thing imagined in his sleep, he cheats deliberately the primal desire at the heart of Faërie: the realisation, independent of the conceiving mind, of imagined wonder.

It is often reported of fairies (truly or lyingly, I do not know) that they are workers of illusion, that they are cheaters of men by ‘fantasy’; but that is quite another matter. That is their affair. Such trickeries happen, at any rate, inside tales in which the fairies are not themselves illusions; behind the fantasy real wills and powers exist, independent of the minds and purposes of men.

It is at any rate essential to a genuine fairy-story, as distinct from the employment of this form for lesser or debased purposes, that it should be presented as ‘true’. The meaning of ‘true’ in this connection I will consider in a moment. But since the fairy-story deals with ‘marvels’, it cannot tolerate any frame or machinery suggesting that the whole story in which they occur is a figment or illusion. The tale itself may, of course, be so good that one can ignore the frame. Or it may be successful and amusing as a dream-story. So are Lewis Carroll’s Alice stories, with their dream-frame and dream-transitions. For this (and other reasons) they are not fairy-stories.

- J R R Tolkien (On Fairy-Stories)

I think the key to understanding this passage might be to recognise that Tolkien seems to be talking more about the writer’s attitude towards the Dream than the Dream itself.

The dream-frame can be very effective in a fairy-story so long as the writer does not diminish the ‘truth’ of the Dream — somewhat like preachiness within a story. If, however, the writer allows a dream-frame to imply that the story is largely nonsensical or inconsequential, they also dismiss the power of Faërie — upon which all fairy-stories depend — and hence place their tale outside the fairy-story category from its conception.

Phantastes and The Lost Road

One of my favourite unfinished manuscripts of Tolkien’s is The Lost Road — a fairy-story with a beautifully elaborate dream-frame. In its opening chapters, we follow the life of a professor of philology as he moves between his waking hours of growing up to become a father and a lecturer and his dream wanderings to the Númenor of the ancient past. The Dream in this story is eventually shown to be a power of Faërie — as it is explained to be a gift he inherited from his distant Númenórean ancestors, who were close in communion with Faërie.

He went back to bed and lay wondering. Suddenly the old desire came over him. It had been growing again for a long time, but he had not felt it like this, a feeling as vivid as hunger or thirst, for years […]

‘I wish there was a “Time-Machine”,’ he said aloud. ‘But Time is not to be conquered by machines. And I should go back, not forward; and I think backwards would be more possible.’

The clouds overcame the sky, and the wind rose and blew; and in his ears, as he fell asleep at last, there was a roaring in the leaves of many trees, and a roaring of long waves upon the shore. ‘The storm is coming upon Númenor!’ he said, and passed out of the waking world.

- J R R Tolkien (The Lost Road and Other Writings); edited by Christopher Tolkien

(In the dream-scene which follows that quote, the protagonist meets Elendil, who grants his wish — to travel back in Time through the Dream, walking in the distant past ‘not […] as one reading a book or looking in a mirror, but as one walking in living peril’.)

I think we can see here Tolkien’s acceptance of the dream-frame in his own Fantasy, as well as a striking similarity to another wonderful dream-frame fairy-story, Phantastes, by the ‘grandfather’ of the Fantasy genre, George MacDonald — where the protagonist falls asleep in his bedroom and wakes on (or dreams of) the road to Fairy Land.

I awoke one morning with the usual perplexity of mind which accompanies the return of consciousness […]

[…] I lay with half-closed eyes. I was soon to find the truth of the lady’s promise that this day I should discover the road into Fairy Land.

CHAPTER II

While these strange events were passing through my mind, I suddenly, as one awakes to the consciousness that the sea has been moaning by him for hours, or that the storm has been howling about his window all night, became aware of the sound of running water near me; and looking out of bed, I saw that a large green marble basin, in which I was wont to wash, and which stood on a low pedestal of the same material in a corner of my room, was overflowing like a spring; and that a stream of clear water was running over the carpet, all the length of the room, finding its outlet I knew not where. And, stranger still, where this carpet , which I had myself designed to imitate a field of grass and daisies, bordered the course of the little stream, the grass-blades and daisies seemed to wave in a tiny breeze that followed the water’s flow; while under the rivulet they bent and swayed with every motion of the changeful current, as if they were about to dissolve with it, and, forsaking their fixed form, become fluent as the waters.

- George MacDonald (Phantastes)

Dreams often carry motifs of chaos or fluidity that can border on seeming nonsensical, and I think it is no accident that both Tolkien and MacDonald described a sound of moving water accompanying their protagonists’ encounter with the Faërie realm through phantasy — and that both phantasies involved images of floodwater destroying (or at least altering) the solidarity or fixedness of land. Phantasy floods and rearranges our perception of matter (or space).

In the dream world, the loss of spatial integrity is often symbolised by a flooded landscape or building. This is usually experienced, on a smaller scale, by the realization of being naked. Indeed, […] clothing is a miniature version of space which “dresses” or “rectifies” the primitive desires of the body. Thus, becoming naked symbolises a return to nature, which comes with feelings of vulnerability from a loss of control over material reality.

- Matthieu Pageau (The Language of Creation — Chapter 62)

The Blood of a Spiritual Wound

Preliminary to the Christian tradition is the idea that in the time of Adam and Eve, humanity sustained a spiritual wound that has afflicted us ever since — an exile imposed because our behaviour is out of line with the reality of God’s good creation, and a homesickness thereafter inherited. To be at home again, to move back into alignment with the good of God’s creation, became one of our deepest desires.

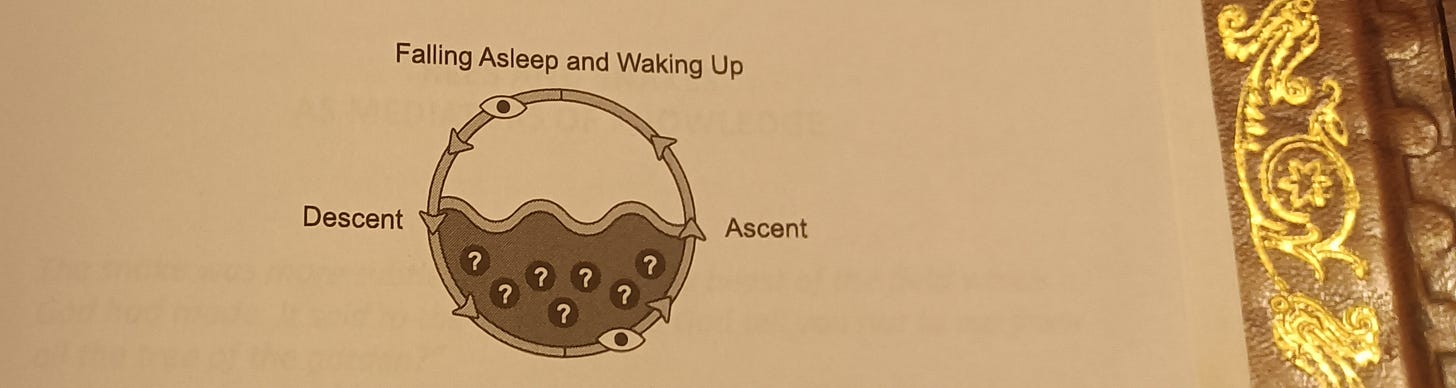

This spiritual wound is bleeding, and, as with any severe wound, the pain we feel intensifies when we pay attention to it and consider its consequences. Dreams are all about exploring consequences and potential remedies, and resting in exile is almost certain to draw our attention to our homesickness because true rest can only find us when we are truly at home. So, as we fall asleep, we turn our gaze upon this weeping wound and dream about its consequences and potential remedies.

Let me put it another way. We were made for an eternal sabbath; for true rest. Our exile surrounded us with wilderness and monsters, necessitating difficult work and provoking restless dreams — it injured our ability to rest. When we try to return to the true rest, it can be like trying to walk on a broken leg; a powerful dream can be like a crutch or a splint.

This is the realm of phantasy, and Faërie sometimes joins in — as an inexplicably external influence or factor. One might not accept the experience of Faërie as an external power until one accepts that his thoughts and phantasies are rarely his own. Once one begins to question where his thoughts (and especially his dreams) come from, one becomes far more likely to experience Faërie.

The kingdom of God is as if a man should scatter seed on the ground, and should sleep by night and rise by day, and the seed should sprout and grow, he himself does not know how. For the earth yields crops by itself […]

Mark 4:26-28 (NKJV)

The Waking Writer

Tolkien’s tales of ‘Home-thirst’ for the Undying Lands of Faërie across the western sea (The Lost Road, especially) seem to be inspired to some degree by his own recurring Atlantean (or Númenórean) phantasy. In Letter 257, Tolkien writes of Atlantis:

This legend or myth or dim memory of some ancient history has always troubled me. In sleep I had the dreadful dream of the ineluctable Wave, either coming out of the quiet sea, or coming in towering over the green inlands. It still occurs occasionally, though now exorcised by writing about it. It always ends by surrender, and I awake gasping out of deep water.

(I’ll leave it to you to consider to what extent his phantasy bore the touch of Faërie.)

In the biblical context of exile, “losing the support of the earth” is usually symbolised by a famine that forces a journey into foreign lands to acquire food. At the internal level, “losing the land” translates as losing the power and support of your own body and its limbs. In the dream world, this may result in an inability to fight back or run from something menacing. It may simply involve a sudden lack of control over one’s body, even to the point of paralysis.

- Matthieu Pageau (The Language of Creation — Chapter 62)

MacDonald’s Phantastes certainly seems to be framed as a man exorcising his own phantasy by writing it down (a phantasy which was itself a kind of exorcism of his Shadow). There is also a motif of phantasy intersecting with Faërie in MacDonald’s At the Back of the North Wind — and much more exploration of the role of nonsense in a dream.1

In Closing

Crucial to these fairy-stories is that, of course, the people involved are touched by Faërie; that the Dream (or dream-frame) is never allowed to imply that the tale is not ‘true’, and that it is never allowed to suggest that our waking life is but another dream (or, at least, not a dream in any sense other than allegory or metaphor).

I’ll leave you with this quote from the final chapter of MacDonald’s Phantastes:

When, at night, I lay down once more in my own bed, I did not feel at all sure that when I awoke, I should not find myself in some mysterious region of Fairy Land. My dreams were incessant and perturbed; but when I did awake, I saw clearly that I was in my own home.

~

Sleep well,

Peter Harrison

PS.

and are currently in the middle of a really excellent exploration of Tolkien’s On Fairy-Stories (here’s a link to the first part). It’s definitely worth checking out if you’re interested in Faërie and the Imagination — and they’ve been pulling in some very helpful additional readings/thoughts from MacDonald, Lewis and Chesterton.Having been on (perhaps) a phantasmic journey to the back of the north wind earlier in the book, Diamond recognises in the thirteenth chapter — in a feverish, dreamy state — that a certain mysterious nursery rhyme seems to describe a river he encountered there.

‘I’m too sleepy,’ said Diamond. ‘Do read some of them to me.’

‘Yes, I will,’ she said, and began one.—‘But this is such nonsense!’ she said again. ‘I will try to find a better one.’

She turned the leaves searching, but three times, with sudden puffs, the wind blew the leaves rustling back to the same verses.

‘Do read that one,’ said Diamond, who seemed to be of the same mind as the wind. ‘It sounded very nice. I am sure it is a good one.’

So his mother thought it might amuse him, though she couldn’t find any sense in it. She never thought he might unerstand it, although she could not.

Now I do not know what the mother read, but this is what Diamond heard, or thought afterwards that he had heard. He was, however, as I have said, very sleepy. And when he thought he understood the verses he may have veen only dreaming better ones. This is how they went—

I know a river whose waters run asleep run run ever singing in the shallows dumb in the hollows sleeping so deep and all the swallows that dip their feathers in the hollows or in the shallows are the merriest swallows of all for the nests they bake with the clay they cake with the water they shake from their wings that rake the water out of the shallows or the hollows will hold together in any weather and so the swallows[… five pages later …]

and all in the grasses and the white daisies and the merry sheep awake or asleep and the happy swallows skimming the shallows and it’s all in the wind that blows from behindHere Diamond became aware that his mother had stopped reading.

‘Why don’t you go on, mother dear?’ he asked.

‘It’s such nonsense!’ said his mother. ‘I believe it would go on for ever.’

‘That’s just what it did,’ said Diamond.

‘What did?’ she asked.

‘Why, the river. That’s almost the very tune it used to sing.’

His mother was frightened, for she thought the fever was coming on again. So she did not contradict him.

‘Who made that poem?’ asked Diamond.

‘I don’t know,’ she answered. ‘Some silly woman for her children, I suppose—and then thought it good enough to print.’

‘She must have been at the back of the north wind some time or other, anyhow,’ said Diamond. ‘She couldn’t have got a hold of it anywhere else. That’s just how it went.’ And he began to chant bits of it here and there; but his mother said nothing for fear of making him worse […] But he soon grew quiet, and before they reached Sandwich he was fast asleep and dreaming of the country at the back of the north wind.

"One might not accept the experience of Faërie as an external power until one accepts that his thoughts and phantasies are rarely his own."

I like what you said here, Peter. So much of modern life is about ourselves: writers write for recognition and book deals, readers read to b personally validated, etc. I think that much like communal music, some forms of dance, etc., Faërie gets us in touch with something bigger than ourselves. It allows us to integrate with, instead of deconstruct and analyze. Really appreciate your sharing your views on Tolkien’s writing; he always has something new to offer.

This brings up that old longing for these worlds to be true.