On the Way to the Beginning: World-Building and Myth-Making

A fantasy focussed reflection on entertainment and sense-making (feat. J R R Tolkien and Matthieu Pageau on myths, recreation, bones and blood).

Mythology is not a disease at all, though it may like all human things become diseased. You might as well say that thinking is a disease of the mind.

- J R R Tolkien (On Fairy-Stories)

(Introduction)

On a road trip with a brother and a friend last year, the conversation turned to world-building — Fantasy and Science Fiction enthusiasts that we are.

A solid hour-and-a-half was devoted to a discussion that sprawled across the fairy-story geography of many different books, films, television shows and Dungeons & Dragons campaigns, inevitably falling into the well-worn topical ruts of ‘hard’ versus ‘soft’ magic systems, character- versus plot-driven narratives and the proliferation of propaganda-corrupted stories released in the last few years. Later that weekend, in a different conversation, the subject would widen to consume the increasingly adverse effects of large language models on storytelling.

Contemplating these things over the last few months, I have found myself more and more convinced that they might all be questions of how you view world-building and myth-making in the Fantasy genre.

In this explorative essay, I’m going to use the term ‘world-building’ to describe the act of sub-creating a ‘secondary world’ out of a ‘diseased’ or ideological understanding of mythology as (primarily) entertainment, and the term ‘myth-making’1 to describe the same act attempted out of a healthy or religious understanding of mythology as (primarily) sense-making. I distinguish these terms with some hesitation. In an ideal world, they would be synonymous, but for now, I need to separate the prevalent contemporary understanding from what I believe to be the traditional one.

The Legacy of Myth-Making (Thesis)

World-building is nowadays generally considered to be the process of building an imaginary world that operates under laws different or additional to our own, but I think that when Tolkien first popularised the idea of sub-creating a ‘secondary world’, he meant something a little more nuanced — something that he described as mythopoeia (meaning ‘myth-making’). Where most postmodern world-builders often focus on crafting realms of new or unique mechanics or lore, Tolkien was more interested in making sense of and re-enchanting the ‘primary world’ in the most traditional and artful way he could — in the legacy of all good myths2.

In On Fairy-Stories, Tolkien wrote that Fantasy should go beyond attempting a ‘willing suspension of disbelief’ and into an ‘inner consistency of reality’; that ‘Fantasy […] does not destroy or even insult Reason’ but ‘the keener and clearer is the reason, the better’3; that ‘we make still by the law in which we were made’; and that:

Probably every writer making a secondary world, a fantasy, every sub-creator, wishes in some measure to be a real maker, or hopes that he is drawing on reality: hopes that the peculiar quality of his secondary world (if not all the details) are derived from Reality, or are flowing into it. If he indeed achieves a quality that can fairly be described by the dictionary definition: ‘inner consistency of reality’, it is difficult to conceive how this can be, if the work does not in some way partake of reality. The peculiar quality of the ‘joy’ in successful Fantasy can thus be explained as a sudden glimpse of the underlying reality or truth.

This kind of storytelling originates in fairy-stories, folktales and, ultimately, myths. Its primary goal from that genesis to the current date is, I think, to make sense of what we encounter in the ‘primary world’. If you think that the ‘primary world’ only makes sense if it is enchanted, then the primary goal is re-enchantment. This makes storytelling fundamental to a Christian way of life.

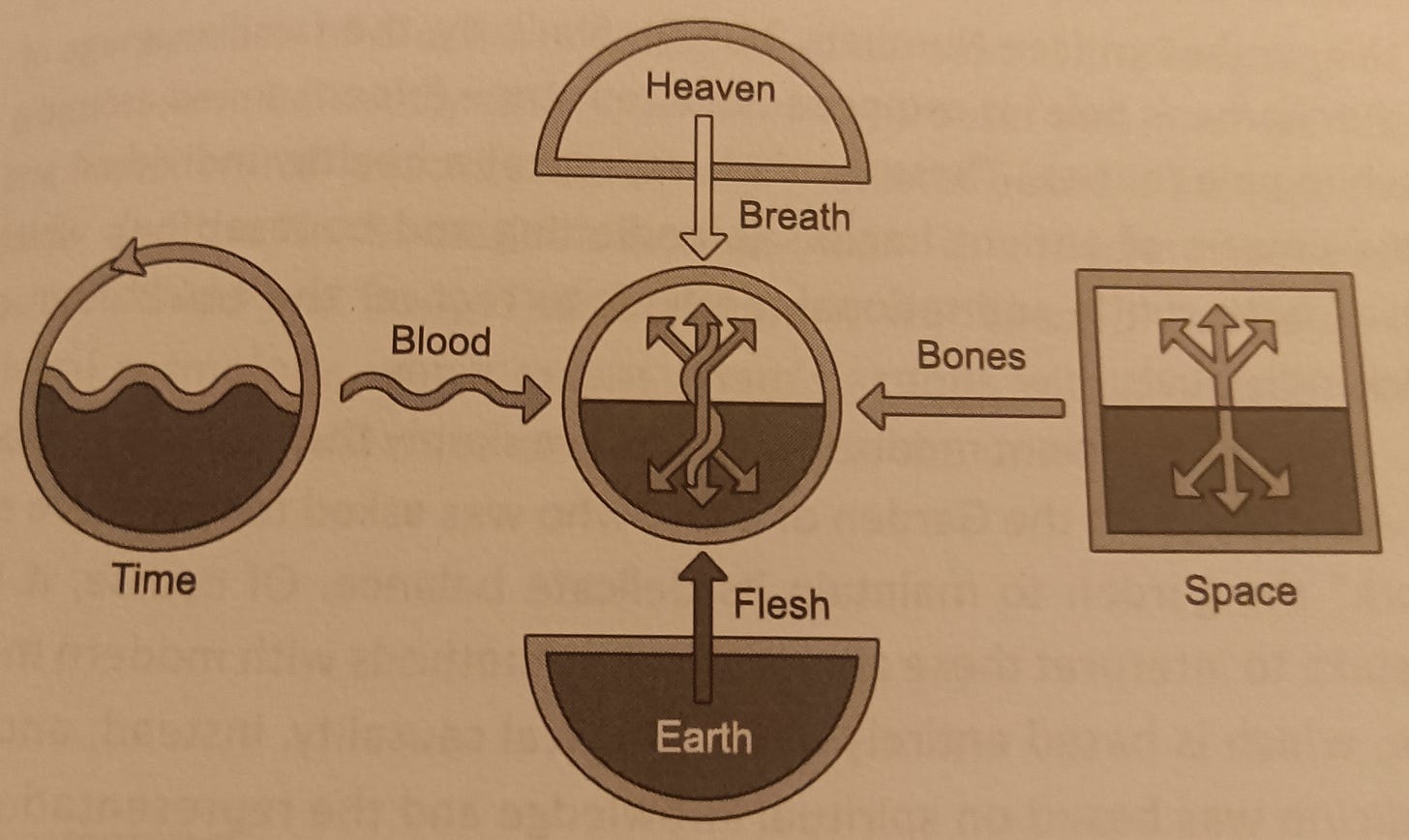

In biblical cosmology, the world was created by the union of ‘heaven’ and ‘earth’, where the first is the source of spiritual meaning, and the second is the source of physical expression. Thus, everything in this universe is analogous to a written word in a divine language.

- Matthieu Pageau (The Language of Creation — Chapter 7)

Language is what separates humans from animals in this cosmology. Adam is the only earthly creature capable of uniting spiritual principles and corporeal facts with language (through his spirit or breath).

- Matthieu Pageau (The Language of Creation — Chapter 17)

The first thing God wanted to see Adam do was tell a story that would make sense of (or enchant) the animals. He wanted to see what names Adam would give to (or find for) the animals; what meaning Adam would give to (or find in) matter; what stories Adam would tell as he attempted to make sense of (or find the essence or essentials of) what he encountered in the ‘primary world’.

Names are the roots — or stem cells — of traditional storytelling. To tell a traditional or mythic story is often to flesh out the meaning or genesis of a name (or a list of names, as Tolkien did to some extent with The Hobbit — the story behind the Dvergatal (the Tally of the Dwarfs) from the Poetic Edda4); to flesh out the meaning or genesis of a name is to rediscover the ‘sense’ that the namer first found in what he encountered in the ‘primary world’.

The Aboriginal legacy of ‘Footprints of the Ancestors’ (‘songlines’ or ‘dream-tracks’) here in Australia pursues the same goal of sense-making in a wonderfully embodied way — as a mapping process. A ‘songline’ was a path long ago travelled by a local ‘creator-being’ who sang out the names of the things around them, bringing them into existence. As a tribe travelled along a ‘songline’, they would sing about how nearby landmarks were formed, the uses of the plants they passed and the stories of the animals they saw — and so doing, they would keep alive the laws and traditions of their tribe which developed out of these stories. To forget your tribe’s ‘songline’ was to forget how you were rooted in and dependent upon your land, your laws and your traditions for your own identity and survival. To forget your tribe’s ‘songline’ was to lose your place on the map; to become lost.

Sense-making is the primary goal of myth-making.

The Saturation of World-Building (Antithesis)

Perhaps a little further (but certainly not a long way) down the hierarchy of goals for good storytelling is the goal to entertain. I’ve come to consider contemporary world-building as a process that begins by placing entertainment or novelty above sense-making, whereas myth-making keeps the traditional hierarchy.

(When a child, or a child-like adult, tells or hears a story, they are naturally most entertained or captivated by the sense-making or re-enchanting aspects of the tale — the hierarchy manifests instinctively.)

Myth-making reaches away from present fads into tradition; world-building reaches away from tradition into ‘originality’. Myth-making is born of a healthy understanding of mythology; world-building is born of a diseased understanding of mythology. Myth-making is steeped in religion; world-building is steeped in ideology.

Now, a story told with a primary desire to entertain may still involve sense-making, of course — in fact, it usually will. I don’t necessarily believe that stories of this kind are bad (they certainly have their place in the margins of the tradition), but Fantasy of this kind has saturated the genre, and large language models will probably only swamp it further. You see, I think it might be the kind of storytelling that large language models will tend towards — or, at least, I think the kind of storytellers who will choose to utilise large language models in their craft will tend towards world-building rather than myth-making.

The saturation is evident to a high degree in the trend of magic in the Fantasy genre becoming increasingly more systematised. For the purpose of his world-building, Brandon Sanderson developed the categories of ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ magic systems to differentiate between magic that followed clear rules and magic with rules less clear. ‘Hard’ magic systems are currently far more popular. (

wrote a great article — Technical & Sacramental Magic — which, I think, provides a more artistic and embodied way of thinking about magic in storytelling.)The fixation of contemporary Fantasy on ‘hard’ or ‘technical’ magic is a symptom of our culture’s diseased understanding of mythology and fairy-stories — diseased in that it comprehends less and less the central importance of ‘soft’ or ‘sacramental’ magic in these stories (it no longer acknowledges the ‘Love, that moves the sun and the other stars’5 and the ‘Deeper Magic from Before the Dawn of Time’6).

And one last example of the saturation is the divergence of ‘High’, ‘Crossover’ and ‘Low’ Fantasy. ‘High’ Fantasy describes a story set in a ‘secondary world’ with no explicit connection to the ‘primary world’; ‘Crossover’ Fantasy describes a story set in a ‘secondary world’ with an explicit connection to the ‘primary world’; ‘Low’ Fantasy describes a fantasy story set in the ‘primary world’.

Tolkien’s Legendarium is often cited as being the original and instigating ‘High’ Fantasy story, but a thorough examination of the narrative framing of The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings and Tolkien’s drafts of The Silmarillion will dispel this notion. Tolkien repeatedly refers to himself in the first person as a translator who found a few accounts of a place called Middle-Earth — our world, long ago. (

has written a few articles — beginning with How Tolkien Disguised Ice-Age Europe as Middle-Earth — which provide another fascinating argument against viewing Middle-Earth as a world completely separate from our own.)The disconnect between ‘secondary worlds’ and the ‘primary world’ that has infused the Fantasy genre further highlights the transition from sense-making to entertainment; from myth-making to world-building. World-builders seek to form clear, concrete narrative frames for their ‘secondary worlds’; myth-makers seek to form invisible frames more conducive to participation (a topic I explored a little in Invisible Frames and Point of View).

Entertainment as Blood; Sense-Making as Bones (Synthesis)

Like the floodwaters that renew the land, blood is a flowing liquid with restorative powers. So, even though the sight of blood is negative when it signals an injury, it also initiates a healing process that returns the flesh to its initial conditions. Therefore, like water, the function of blood is to “wash” in the sense of refresh and renew. This contrasts with the dry bones, which are the pillars that stabalize and uphold […]

- Matthieu Pageau (The Language of Creation — Chapter 54)

I have a feeling that the saturation won’t last. The pervasion is perhaps yet another indication of the simultaneous and paradoxical excess of sanitisation and chaos in our culture. Blood and wine are symbols of both of these superfluities. The blood that cleans and purifies the world does so only because it is disorder and potential poured over the pursuit of stony stagnation in contemporary science (the pursuits of ‘technical’ magic). The chaotic entertainment of world-building might be an attempt to cover our culture’s stagnated scientific worldview … But, once we’re bathing in this ‘entertainment-blood’, we might begin to realise that no amount of the liquid will be able to penetrate and purify the stony structure of our culture’s ‘science-bones’.

Just as our blood cells are mostly created in the marrow of our bones, so the entertainment of storytelling should be rooted in its sense-making. The traditional, hierarchical, structured method of myth-making might be the bones we need to rediscover and make use of — the living ‘myth-bones’ that the ‘entertainment-blood’ can return to, perforate and cleanse properly. Rather than a bloodbath, we might only need a taste to sustain us. Our culture’s vampiric thirst for entertainment will meet the crucifix at the heart of The True Myth — The Living Paradox of the Incarnation …

[…] it is important to remember that wine is only a mild poison, and it was not created to bring total death to its drinker. Instead, humans willingly subject themselves to this benign form of “death” for distraction, rest, recreation, and renewal.

- Matthieu Pageau (The Language of Creation — Chapter 80)

For Want of a Good Story (Application)

All this to reiterate: I have a hope that the situation won’t last. Perhaps the use of large language models will take storytelling to such a point of entertainment-based world-building that more and more folk will realise they’re longing for something more edifying and go searching in more traditional, mythic places … And their checking-out of poisonous entertainment-based storytelling will bankrupt the business and … and … Well, maybe. I hope.

It’s likely to be a lot more difficult than that. Storytelling has begun more wars than any other human activity — and ended more as well. Sense-seeking myth-makers will need to step up to the plate.

The propagandists know a thing or two about myth-making, and they’re hard at work. Their version of sense-making is to lean into half-truths and lies with a desperate, vain hope that their dedication will make their pathological ideology true (a topic I touched on in the postscript of Sermons and Speeches).

And he humbled thee, and suffered thee to hunger, and fed thee with manna […] that he might make thee know that man doth not live by bread only, but by every word that proceedeth out of the mouth of the LORD doth man live.

Deuteronomy 8:3 (KJV)

The world is eating stone and bathing in blood for want of a good story.

Here’s to those stepping up to the plate.

~

Until next time,

Peter Harrison

Throughout this piece, I use ‘myth-making’ rather than ‘mythopoeia’ because the former is the term I most often think with, and it fits more comfortably into an informal essay.

Check out The Underworld, the Otherworld, and the Upperworld, by

, for a brief investigation of the nature of Fairyland, which expands on the idea of mythopoeia being the process of recording what our imagination senses.A more extended quotation of this passage from Tolkien’s On Fairy-Stories:

Children are capable, of course, of literary belief, when the story-maker’s art is good enough to produce it. That state of mind has been called ‘willing suspension of disbelief’. But this does not seem to me a good description of what happens. What really happens is that the story-maker proves a successful ‘sub-creator’.

[…]

Fantasy is a natural human activity. It certainly does not destroy or even insult Reason; and it does not either blunt the appetite for, nor obscure the perception of, scientific verity. On the contrary. The keener and clearer is the reason, the better the fantasy will it make. If men were ever in a state in which they did not want to know could not perceive truth (facts or evidence), then Fantasy would languish until they were cured.

See the first chapter of J. R. R. Tolkien — Author of the Century by Tom Shippey for more on this.

From Dante’s Paradiso.

Chapter XV from C S Lewis’s The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe.

This was a good read. Sorry for replying so late (you've posted this months ago), but I wanted to address it / ask questions.

1) Could you give examples of what you mean by the thesis, antithesis and synthesis? As an additional conditional, I say you cannot use Tolkien or Lewis. I'm asking this because a lot of time we revert to Tolkien's work as the prime definition, but it's kind of cheating if he's the only one that ever managed to do it. We have very few examples of pre-Tolkien 'fantasy' (proper), such as A Voyage to Arcturus by David Lindsay, the Worm Ouroboros by E.R. Eddison and The King of Elfland's Daughter by Lord Dunsany. Any of those qualify for you? What about post-Tolkien?

2) What do you say is the path forward? How do we go from antithesis to synthesis in this case?

3) If we get in the details of worldbuilding/mythmaking for participative agency (something like role-playing games), I could lay out different ways of doing it:

- Christian World: A world akin to our own (either directly or indirectly) that's set in a post-Christ world. Sometimes you'll have low fantasy / historical fantasy in this category.

- Christianized Myth Making: The world is a christian creation, but Christ is not present. This is where I'd put Tolkien's works.

- Christian Story: The world is generally created as being separate, but the focus is on a story that is itself christian in themes, terms and values.

- Christian Allegory: It can be 'on the nose' (1 for 1 of major figures and themes) like Lewis, but it can also be more 'structural' like what Father Dave (an orthodox priest playing D&D and other TTRPG) did with his fantasy campaign. I cannot link to everything, but this is an example: https://bloodofprokopius.blogspot.com/2018/12/mathetes-to-diognetus-chapter-7-part-2.html And here are some additional resources: https://bloodofprokopius.blogspot.com/2023/04/on-gods-and-rpgs.html https://bloodofprokopius.blogspot.com/search/label/Deities%20n%20Demigods https://bloodofprokopius.blogspot.com/2020/08/world-building-with-noahide-laws.html etc.

There's probably more categories and so on. But my point is that I'm curious as to where we can/should stand as subcreators. In each category I propose above, there is a distinct function of the subcreators in relation to its subcreation ("world", "myth", "meaning"), but also to myth-making itself as an activity. I was wondering if you had thoughts on this.

4) Related to all previous questions, what would be the boundaries of meaning-making vs entertainment making? How does one knows if he's doing one or the other? How does a "world" become a "myth", or a "meaning" becomes just "entertainment"?

I'm genuinely asking those questions btw, I'm just interested in this topic and how you view it.

Thus aligns with where I have arrived in my own fiction writing. I am particularly enjoying magical realism as the genre that brings me closest to creating a world which allows for faith and spirituality to become tangible.